My time living on Everhart Street in Atlanta, Ga., from 2014 to 2018

There are two ways I can begin telling this story. Both are unsettling.

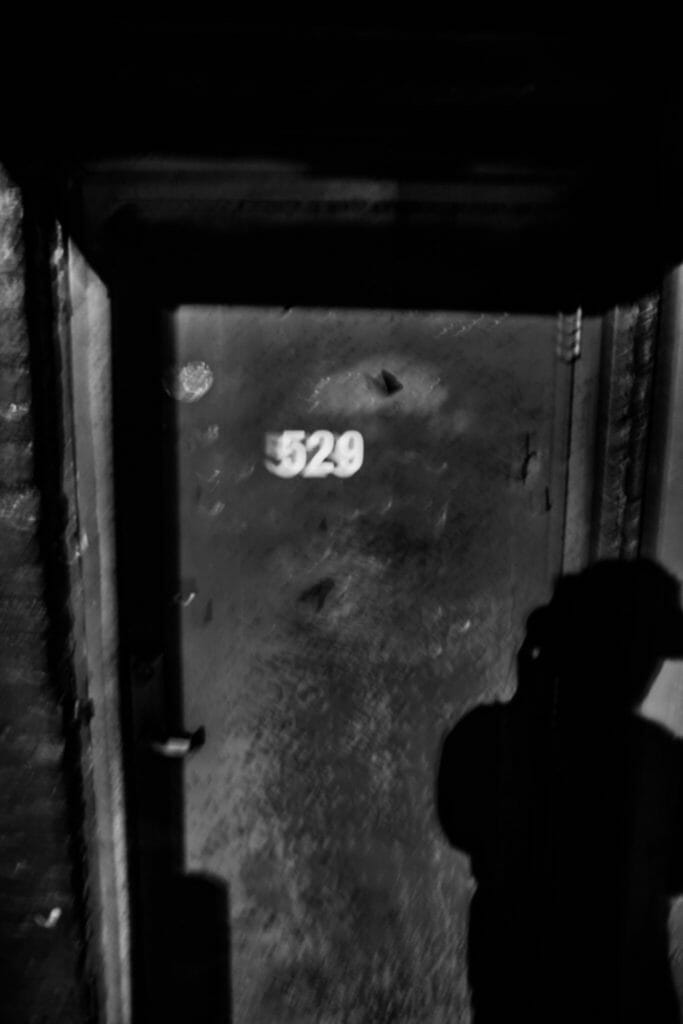

Either: My home was robbed by my seemingly best friend’s new boyfriend in Decatur, Ga., while I was in California visiting my dying Aunt in hospice. There was nothing left when I returned; not even my housemates. The only sign they ever existed was a bobby pin on the floor. I was no longer home and needed to go. I then moved to Everhart Street in the Pittsburgh community of Southwest Atlanta. It was my home between 2014 and 2018.

Or: On the night of June 12, 2020, Rayshard Brooks was murdered by that cop who squealed “got ‘em” when he shot him in the back. His partner stood on Ray’s shoulders as he died at the Wendy’s on University Avenue, which is right around the corner from my old house on Everhart Street. I used to go there all the time.

Regardless of a genesis story, the untimely deaths of Ray, 8-year-old Secoria Turner, and an unidentified Black man dying by triple crossfire, in a triangle of intersecting corners of a gas station, drive-thru, and time itself, brought back memories that would probably be defined by many as unbelievable.

Firepit gatherings and boozy impromptu living room music festivals made my house the loudest on the block on Everhart Street, but no one ever complained. To the left of my house was a short walk to one of the entrances of Perkerson Park. It had an earthy, oasis feel to it due to the height of the trees, walking paths, and creek that housed every mosquito in the area. The Morehouse College baseball team practiced and played home games on the upper hillside, and a frisbee golf course formed throughout those tall trees, banking around the top to bottom. I played kickball, worked out, drank, walked the dogs, smoked, ate sandwiches, took turns on the swing set, made art, witnessed shoot outs, ran through water shoots with the local kids, and spectated huge BBQ parties during a regular summer.

The City of Atlanta took care of the grounds at the bare minimum, even though the area is described on the Beltline’s official website as a “gem.” It was in a Black neighborhood, after all. I imagine Perkerson felt like a throwback to inner-city life before we became obsessed with privacy when public resources reigned supreme. I’m assuming a communal utopia; this is, of course, an assumption based on what I’ve seen in movies and TV shows.

This might be a good spot to note that I am a responsive communitarian by nature. My life path number is six. Family is my happy place and village is my dream.

As a response to the community’s desperation to put an end to police brutality, I became an organized activist and held group meetings in the outdoor pavilion in the park that rotated between birthday parties, baby showers, and traveling churches.

Ms. Carole would bring her grandkids to the park to play while she used the outlets in the pavilion to charge her phone. Bursts of gray hair in her lengthy locs were an indication of her age paired with a dull whiteness in her eyes. Her back kept a slight bend. Her voice sounded tired. Blue was a nice color on her. Her skin was brown with a hint of ash like a cigarette bud. Looking at her it was clear that she bends more than she should, but never quite breaks.

She told me about the old people around who had cancer, tumors, and chronic pain, but couldn’t get any medication or insurance; so they turned to crack to relieve their suffering and then got hooked. She told me about the children who were sold off to other families in the area and then carried on her conversation, nonchalantly acknowledging the horror as if it were general knowledge. We agreed that we didn’t trust the pastor from Texas and his wife who offered pancakes with sermons on Sundays and welcomed neighborhood kids to wash their clothes at their home. She didn’t like that they were touching their underwear. We would sit together at communion every week before the activist meeting. Ms. Carole and her grandkids would stick around for a little while. Every time my gaze met theirs I was well aware of the reality that in trying to change the world, I ironically didn’t know how to help them at all.

To the right of my house, was the stroll on Dill Avenue. The star of the show was Tiny. She was a shapeshifter. From the back, she was a pin-thin, hourglass wonder with a wide thigh gap and bouncy hips. She had a quick walk that always made her look like she was late for something. From the front, her face looked like a drawing of an old witch in a Grimm’s tale topped off with an orangey mohawk. No one worked harder than Tiny. If you didn’t see her pacing for more than a day, she was locked up.

Down the hill was the Chevron where getting a pack of Newports after dark meant walking through an auction of random men whispering their dollar bids for meeting them in the bathroom. That’s where I got gas, squares, twenty-twos, and little bags of munchies. Day time was a different scene. Before you made it to the door, little kids with torn-up, oversized clothes on bikes would approach you and emptily say, “I’ll do whatever you want for a dollar.”

The first time it happened, I pulled a boy to the side and begged him to never say that again or he’ll get taken advantage of by the wrong person. His eyes were big and beautiful looking back at me while he rode away. We crossed paths constantly, but I never got his name. He just kept saying he would do whatever for a dollar until he disappeared.

The police were like horse flies on a lake that bite you right when you get your head above water. Our blocks were the perfect quota-grab heaven. Random roadblocks at University and Metropolitan to check vehicles looked like a game of “Simon Says.” Patrolling kids on the playground at the park was normal. Tailgating you at night with all their lights off, including headlights, was a weird, frightening, and dangerous game they liked to play right before they pulled you over.

I remember the time I called them over a domestic situation, which was hypocritical to everything I had been protesting about. I was nervous as hell. I had no reason to trust them, but I needed help. I told them repeatedly that no one was armed until semantic satiation set in. Upon leaving, the officer thought it would be a good idea to block me from closing my door to ask for my phone number. Maybe that’s some sort of perversion of community policing that fits into their policies. My tax dollars mattered as little as helping me feel safe at that moment. They didn’t work for me. Their bosses were the New Pioneers who had come to stake claim on land that didn’t belong to them.

I remember seeing a white man jogging one night by my house and I thought he was crazy and couldn’t have known where he was. Then, I saw the American flags pop up over a few doorways and knew something was changing. The mural by the community garden that beamed with the beautiful brown faces of children who lived among us was painted over. The NPU-X meetings were filled with gentrifiers requesting more police presence for kids coming off their school buses in the afternoon.

They were scared of the kids. The gentrifiers engaged in supposedly civilized discourse over the homeless shelter that was being built, claiming it to be too close to the border of our area, which they feared would change their property values. I saw white women walking their dogs casually early in the morning. They didn’t know they should carry a stick to ward off strays.

My immediate neighbor, José, and his family were hustled by that creepy Texas pastor and his wife. José’s house was falling apart in dilapidated purple favela-style glory. He sold it for $30,000 and left. Renovation was next. Construction started, and I would bring the workers ice water on hot days and we’d talk about materials. It was around a $60,000 renovation. I saw online that Texas sold that house for $238,536. I knew that when my landlord found out, I was going to be the next in line to leave. I remember being angry at José for not knowing any better and for walking away with pennies on his elephantiasis ankles. I wanted his family to be well; at least he got something, I guess.

Texas had a few members from his congregation migrate into the neighborhood and push out others like José simultaneously. One day on a pause from an afternoon run, I was mortified to watch a couple of gentrifiers film for HGTV with their perfectly remodeled home painted in the shade of colonialism. The B-roll had to be a fairytale of proportions. The neighborhood app, Nextdoor, was where new pioneers felt free and safe to call Black kids “POS” for running on their picturesque manicured grass. When I suggested they leave since it was so bad and to never speak of children like that again, I was told I was mean and that I had made one lady cry. The irony of dissonance never ceases to amaze me.

Whitewashing isn’t solely for history books. Amongst other things, it’s also an act of equity terrorism. Dehumanization was a big, gray controlled cloud over Everhart Street and all her sister blocks in Pittsburgh, “A Weed and Seed Community”. Generations under one roof surviving in a fishbowl were only as useful as they were exploited.

After four years of living there, my landlord refused to fix a flooding issue in the house any longer and suggested I leave instead. It was time for him to do the flip. I moved out exactly a week before all the home invasions began. There were so many at once that it made the news. The natives were fighting back, and I was happy they weren’t going down without a fight.

I knew first hand what it felt like for your home to be violated, and so did they. The only difference is that the violation of their lives and homes continues to be legal and promoted as progression. They won’t enjoy the clean streets, new shops and jobs, millennial markets, and a sparkly Perkerson Park “located a few blocks south of the future intersection of the Southside and Westside trails of the Beltline.” Years later, all my voting, protesting, demanding, donating, learning, and hoping still hasn’t helped them one bit. I only have their stories to tell, and I don’t know if I’ve done them any justice.

Per usual.