Photography by Richard Martin

Recently, East Atlanta venues 529 and the Earl played host to the fourth annual Irrelevant Music Fest, a showcase of mostly local performers associated with Kyle Swick’s record label and promotional arm of the same name. Swick—whose duties also include booking 529 and other local venues—has become a key curator of the Atlanta scene. And although Irrelevant’s acts work across many genre lines (and individually often bend, blur, or ditch those lines entirely), a consistent (albeit difficult-to-thumb) strain seems to run among them.

Case in point: at first glance, the bill for the fest’s second night appeared to be a potentially dysfunctional spread of genres. Two hip-hop acts folded in with a couple of punk bands, an indie quartet playing jazz chords, and a Latinx expression power trio—nearly a mishmash. If one didn’t approach the night with a measured dose of trust in Swick’s ability to assemble a lineup, it would have been a little worrisome, but the night was hitchless. What did Swick know that we didn’t? How did this coagulant operate?

Well, one explanation is that most of the artists themselves already wander among genre lines. At times, the mixture was between elements that aren’t terribly far apart, but also don’t usually appear side-by-side. For instance, Harmacy played a strain of punk that took early grunge and paired it with vocals semi-reminiscent of ‘90s hardcore. Imagine the throaty, echoed peals of, say, Strife, over, say, Mudhoney, or the heavier moments of Bleach. (Note: it’s a substantial improvement over regular old there-is-only-one-song Strife.) To add more to the tapestry, vocalist Brandon Reid stepped onstage dressed in a look one could call “it’s 1989 and he’s dad on a boardwalk,” complete with straight blond mullet, long jean shorts, and tube socks. But—with his delivery intense and the music driving and fierce—the comedy of the getup melted down into useful oddness. Taken together, the band’s feeling was one of a composed, complete thing, but not exactly seen before. There was just enough of the strange to balance the familiar, and although you were left wondering how much was kidding vs. serious, you never doubted at any level that Harmacy meant it.

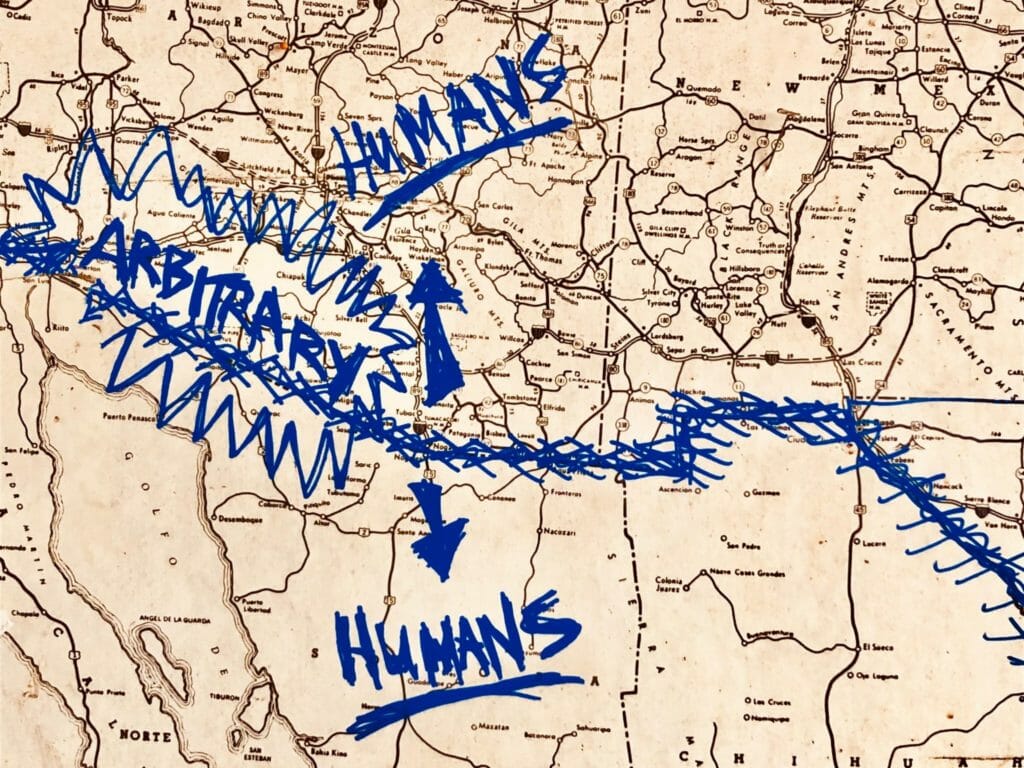

A second reason the bill worked was the somewhat recently-installed 529 PA. It has a ton of low end. Like, so much. That, along with the overall mix that night, fully rewarded the work of the various rhythm sections. Miranda Corless’s bass (of Kibi James) sounded unreal. It was thick, but also clear and—well—like an actual instrument, not just a noise, melding in perfect touch with Ariana Abebe’s kick pedal. Hannah Lenkey (bass) and Danielle Dollar (drums) of headliners Yukons were dead tight, and supplied a ton of groove for singer/guitarist José Izaguirre to do that Westerbergian, mop-haired thing, which, at times, like Harmacy, had moments of real distinction, using a somewhat straightforward genre (that being a punky rock ‘n’ roll) as platform to express identity as Latinx. Mind you, this isn’t a “Latin-sounding” band. It’s a band about being Latinx, which is its own subversion of genre and how genre works, and in the moment provokes a thought or two.

But the bands were all fairly thumpy, and it was hardly a stretch when the 808s etc. came on for the five months pregnant Lord Narf, who—in a high-hitched, luminous babydoll tutu—was as rowdy as she was resplendent, and bore onstage a mixed squadron of other hip-hop artists, complete with side-stage moral support lent by indie singer and Awful Records alumni Faye Webster, who herself has bent a genre or two, and a guest spot by Atlanta rapper and LGBTQ advocate Ripparachie. One further subtle point here: the music in-between all sets was almost exclusively hip hop, which seemed to help the aesthetic balance over all. It was a good, harmonious glue.

A third explanation for all this is simply that Swick seems to have a keen eye for tangible energy. Even hip-hop artist Jamee Cornelia, who opened the show in the very unlucky 8 o’clock slot—a time when no person in the village is walking into venues—brought all possible zeal to the dozen or so bodies in the room. Upchuck—a band that rides mostly on hardcore motifs, but whose onstage style looks like a cross-section of Atlanta sorts and could even serve as poster child for this article’s theme, namely of an exhilarating reality where racial/cultural identity and genre and all of that potential nonsense has the ability to crumble into an appealing pile of inspectable scraps of human fervor—kept a mosh pit alive their entire set. Ultimately, not one of the acts failed to make people dance.

If that night had been a bill full of bands sticking to crisp formulas, the lines between them might have been difficult to cross (a punk crowd files out; then a hip-hop crowd replaces them, and yada). But those days have evaporated and been replaced with a fandom that is very genre-literate. More and more, I think genre-at-play might lately be the lion’s share of the entire expressive thing of musical art. It’s nonsense, for sure, but keeping tabs on the vocabulary—and the dialogue wherein it flourishes—is a vigorous kind of fun.