“May our tears

Rehydrate the

Forgotten spaces

& beings long

Forgotten … hidden

underground

May our voices

rise us all up

May our prayers

Feed us all”

– Anonymous prayer at Tatiana Bell’s “We Keep us Safe” installation

A police officer’s walkie beeped. He stared ahead without seeing — surveillance. Police car engines idled a low threat. Officers were stationed on both sides of the road. I felt their gaze, a constricting force. The body harder to move forward, the breath tighter in the body, I leapt over the shoulder of the road. I wanted to get a closer look at the spider webs connecting wild growth, in the light of the golden hour. Hello, giant orb spider weaving between green.

It was late October, and I was on my way to a queer grief ritual, a space for queer people to mourn in community. I walked down Key Road, past the site of Cop City construction. I was hidden from the main road, on the forest side, closer to the trees. I was afraid of a cop car driving by, especially if I seemed like I was emerging from the woods. What reasons would they give for stopping me, asking to see my ID? Then I felt angry. I stared into the darkened windshields of the officers. They were probably staring back. What did they, hidden safely in their patrol vehicles, fear? Was I inside of their web, creating tremors on their patrol lines? Spiders anesthetize their prey before wrapping them in silk. Maybe, I thought, I was prey that escaped, trailing bits of web behind me. Exiting the police perimeter onto Fleetwood Drive, I realized there is no spider. This web — the Cop City project, one strand in the police industrial complex — catches nothing but itself. Its edges curl inward with the breeze, sticking to its own broken pieces and torn holes. The spider is the shadow in our periphery, the distant sound of heavy machinery tearing down trees. None of us, police nor civilians, truly walk free. But we are numb to that. We are wrapped in our grief.

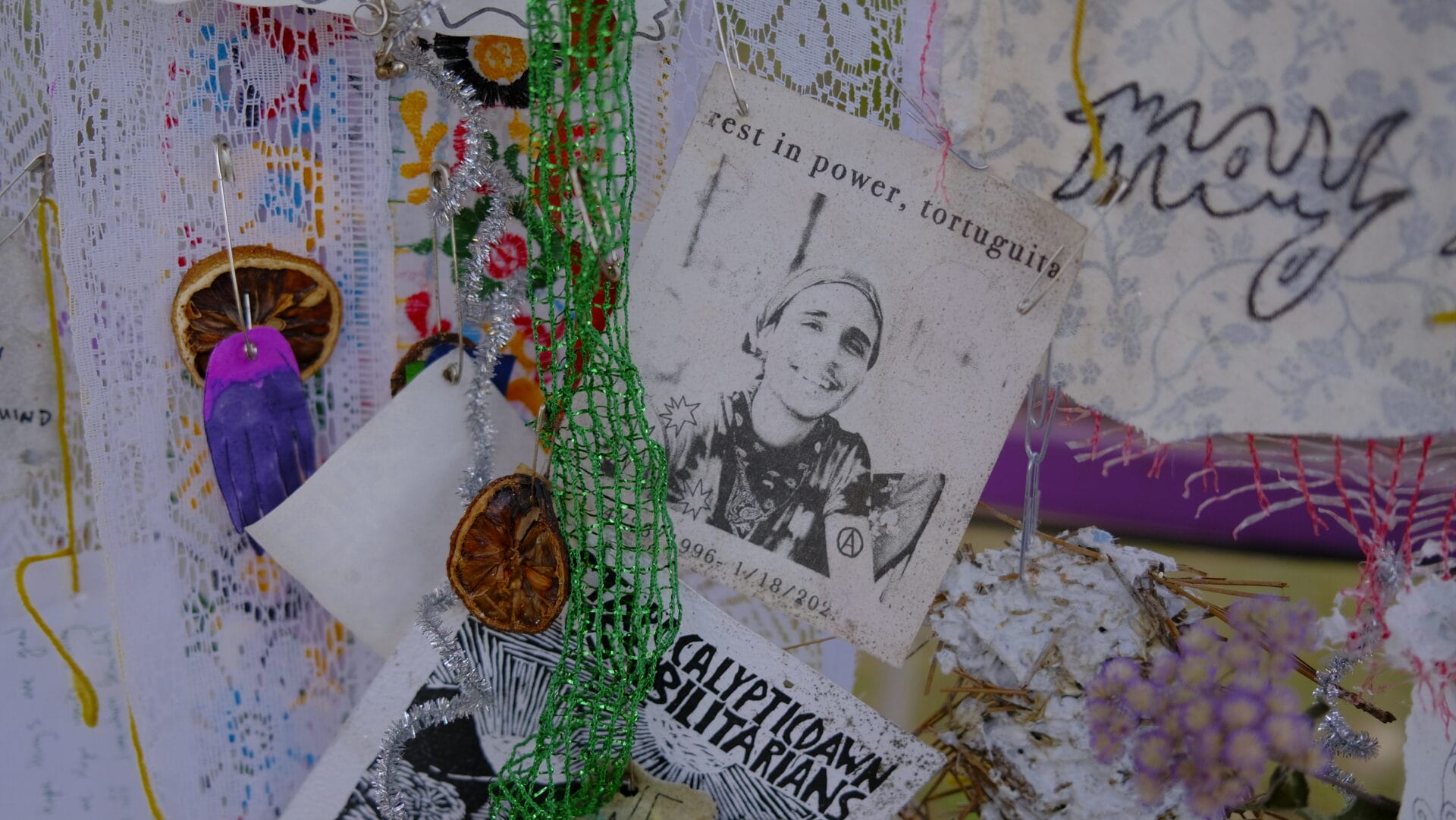

A lifelong Atlantan, I got involved with the movement to Stop Cop City during the Weelaunee encampment of summer 2021. Largely occupied by queer anarchists, Intrenchment Creek Park became “Weelaunee People’s Park.” It was the first time I understood mutual aid as an operable system. My trans siblings were not “outside” of any norms, and no one was without shelter or food. I saw the power of anarchy as rebuilding, world-making to survive a culture of death. Much like spider webs, the camp’s existence was fragile. We were the tender green shoots holding it up. I remember falling asleep in my tent to the sounds of summer rain, of a dance party on one side and the echoes from the police firing range on the other. The camp grew in spite of an imminent sense of destruction. Then, its temporal beauty was destroyed by military-style forest raids. Police slashed tents, razed the garden, and churned the sidewalks into rubble. On January 18, 2023, Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán, a queer environmental activist, was killed by police. We as a community began to grieve.

In September, Maya Wiseman’s intuition woke her up in the middle of the night, telling her she needed to host a grief ritual for queer people. Wiseman, a Black lesbian performance artist, is an organizer for Southern Fried Queer Pride. “I went back to sleep, and I woke up and started planning,” she said. She reached out to mixed-race queer artist Tatiana Bell, and after weeks of preparation, they hosted the ritual at the South River Arts Collective (SRAC). Wiseman and Bell encouraged attendees to place offerings in a small, lopsided house that Wiseman had built with mixed media artist Maggie Kane. The shape of the house, Wiseman said, “felt like a metaphor for grief.” Made of scrap materials, the house’s slanted roof and imperfect open design wasn’t pretty, but that was the point.

Wanting to shoulder the weight of our collective grief, Wiseman hoisted the house onto her back and led attendees to a roaring fire. We watched the house burn and screamed into the flames. Wiseman and Bell had created an intentional space that centered queer, BIPOC grief. Grief caused by housing insecurity, lack of bodily autonomy, and broken relationships with loved ones. Bell said the losses in queer, BIPOC lives, “leave a lot of room for community building in our own ways.” The amount of physical connection that night surprised Wiseman. “I have not been hugged and held so many people at any event that I’ve had … in a long time.”

Later in the night, Leopoldine and Jasper, a queer performance duo, wove a line of golden rope through each of our hands until we were all connected. They danced in the center of our circle around a pot of soil surrounded by candles. Then, they reeled in the rope and invited each of us to take a seed and plant it in the soil. All of the rope collected, Leopoldine and Jasper stretched it between them. They’d made a spider web with our shared rope. I thought about the abundance of spiders I encountered on my walk there. I thought about how this grief ritual connected to past and and future ones. These healing spaces allow us to unwind the grief that binds us and create something new with the lines. Before it was over, attendees were asking Wiseman when her next grief ritual would be.

***

Earlier that fall, I was invited to be part of an intimate healing circle with fellow members of the Stop Cop City movement. It was September 5, 2023 the day Atlanta Community Press Collective exposed Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) charges against 61 people in connection with the Stop Cop City Movement. The same Fulton County courtroom criminalizing activists also indicted Trump and his affiliates on RICO charges for election interference and is currently trying rapper Young Thug’s YSL group for murder, carjacking, and more. The Stop Cop City indictment document defines solidarity, mutual aid, and the collective as fundamentals of anti-authority anarchist violence.

Lavender, a queer artist who uses a pseudonym as a member of the movement, coincidentally planned the healing circle for the same day the news broke. “We were dealing with the grief of witnessing state repression firsthand on such a violent and personal level,” she said. She did not want to be alone with that grief. One attendee is currently facing RICO charges. Lavender asked them what weighed heavily and how the circle could lighten the load. We shared words of love and encouragement. We held each other. We shared a meal by candlelight and smoked each other’s cigarettes. Lavender’s mind was blown by the power of asking for support and simply receiving it. She felt a new sense of safety. “One of the only times I’ve felt that in my life, and it was all because I asked for it,” she said. “I could feel other people needed it too.”

***

A picture of Tortuguita hangs in the VRT lab — vrt means “garden” in Slovene — at the SRAC. The lab, a collaborative space, sits in a small greenhouse built by Kane. Situated next to the Cop city construction site, the lab is deeply rooted in place. String lights adorn its roof. A disco ball hangs from the ceiling. Tort’s memorial is part of an installation by Bell. The VRT lab’s windows are painted with the installation’s title, “We Keep Us Safe,” and words of loss and healing abound. An online version of the exhibition allows viewers to scroll through a tapestry of grief. Words that hang in the physical space scroll across the screen, shifting between lowercase, uppercase, vibrant and muted hues. Some messages honor Terán’s legacy: “May Tortuguita be a flame that burns down every prison and precinct.” Other messages are of hope and community: “You are not alone.” Bell created from collective grief, she said, to “listen to what everybody else is saying.” She installed Tort’s memorial in the lab just before the October grief ritual.

“The way we love each other and show up for each other and support each other, that’s how we win,” Lavender told me, “and that’s something the state can never take from us.” The futures of the Stop Cop City Movement and the Atlanta queer community rely on each other’s webs of support for mutual growth. I reimagine the shadowy spider in our periphery as the spirit of Tortuguita, connecting us in a powerful web of grief — and action.

On November 13, Block Cop City organizers led a mass nonviolent direct action, a manifestation of how we care for each other. We marched down Constitution Road toward the Cop City construction site. “I love you, you love me, we love Weelaunee,” we chanted. Members of Wambli Ska Okolakiciye, a Native-led cultural preservation organization, began a prayer song. We formed a circle around them. Hundreds of us held puppets and balloons against a line of police decked out in riot gear. We charged ahead, arm in arm, our bodies against the police batons and shields. They threw tear gas and smoke grenades. Medics and friends tended to us, our eyes and throats burnt. As we marched back to our starting point, comrades planted native tree saplings along the route.

We returned to our community joyfully, to the music of the marching band. We danced on the trail to Weelaunee’s People Park, now closed to the public. I glimpsed that old Weelaunee web — a world of mutual aid in the woods destroyed. The RICO indictment document describes anarchists as “weavers,” who integrate terms like solidarity and collective “into their jargon and writings.” We as a collective, anarchist or not, weave with our grief. We weave worlds within a world, in the dying light of state repression. If there’s a message to be read on our web, it appears fleetingly, but it holds true: We keep us safe.