Letters and interview obtained by The Mainline shows ICDC staff mix symptomatic individuals with general population, refuse to protect detainees from COVID-19, among other human rights violations

OCILLA, GA. — Three different housing units at the Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC) in Ocilla, Ga., have gone under lockdown in the last week due to outbreaks of COVID-19, according to an official press release sent from the Community Health Law Partnership at the University of Georgia.

ICDC, which is run by the private corporation LaSalle Corrections and contracts with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), is the same detention facility to come under fire for allegations of medical and gynecological abuse conducted on female detainees by Dr. Mahendra Amin, who was also contracted by ICE, and other detention officials last year. Former nurse Dawn Wooten blew the whistle about the abuse last September, sparking widespread (albeit relatively brief) national attention towards the detention center and its ongoing issues of abuse and neglect.

Advocacy groups filed a class action lawsuit on the women’s behalf last December. Those cases are now pending before the middle district of Georgia in federal court before Judge W. Louis Sands. There are 14 plaintiffs currently involved in the litigation regarding the medical abuses at the facility, and advocates involved in the case have filed a massive complaint to prevent ICE from retaliating against the women coming forward.

The press release — dated Sat., Feb. 13, and primarily authored by Samantha Hamilton, Legal Fellow in the First Amendment Clinic at UGA Law — states that officials at ICDC have neglected to test recent transfers who have exhibited symptoms of COVID-19. The release goes on to say that officials have then mixed these individuals with the general population, failing to mitigate the spread. This COVID-19 outbreak is only the most recent development in the poorly run detention center where abuse, malpractice, and deteriorating conditions were commonplace prior to the global coronavirus pandemic and the surfacing news of medical abuse last year.

I met in a virtual interview with Hamilton, Jason A. Cade of Community Health Law Partnership Clinic at the University of Georgia School of Law, Ariel Prado of Innovation Law Lab, and Cathy Carrillo of Southeast Immigrant Rights Network, who confirmed the details in the press release as well as elaborated on the conditions of ICDC. Names of those detained in the facility who shared their experiences remain anonymous as to protect them from retaliation for coming forward.

“People in detention in the Irwin County Detention Center are being retaliated against for their speech when they speak out about a slew of things,” explains Hamilton. “Most prominently right now are the complaints about proper health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. People have been speaking out about this over the last year and they’ve consistently been retaliated against through physical beatings, through having their phone calls surveilled and cut off, things like that.”

Hamilton says she received news of the COVID-19 outbreak in the facility mid-week last week and has been spending her time tracing detainees’ stories. She conducted direct interviews with individuals being held in the facility, which are detailed and sourced here. Given how the facility is run, it’s become difficult for detainees to communicate their experiences with the general public or even each other.

“People inside the prison are also intentionally separated from one another so that it’s hard for them to share information with one another,” says Prado. “Towards the beginning of the pandemic, the decision was made to not tell anyone on the inside about COVID, because they didn’t want people to panic. They didn’t provide masks to people, because they didn’t want people to panic. They didn’t even provide masks [or] PPE to the guards at first … and then slowly, through a lot of organizing on the inside by people who are detained, and through advocacy efforts of many attorneys and organizers, there’s been a push for there to be access to PPE on the inside.”

Prado clarifies that it was then private donors that donated PPE to the facility and that those masks “have been the only masks that people on the inside have access to for prolonged periods of time.”

Prado explained in detail that detainees are not only left in the dark about other individuals’ diagnosis or treatment through being separated from one another, but that guards also withhold important information regarding health concerns from those detained in the facility. He also emphasized that detainees are not regularly tested and are barely monitored for symptoms by personnel or medical practitioners.

“They’re having to piece together who has tested positive for COVID, because the guards aren’t telling them,” he said. “Somebody gets taken to medical and then they never come back. The guards pack up their stuff or direct the folks in detention to pack up their stuff, because the guards are afraid to touch it.”

This isn’t dissimilar to how the detention center treats its detainees in regards to legal action pertaining to their cases, either. Prado told me of a man who was called in for an ICE check-in back in 2018 after he received a letter in that mail that instructed him to come to the ICE office.

He went and they said, \’We noticed you have a DUI from 2010,\’ continues Prado. They made the decision to detain [him] and he\’s been detained since. The language they use is the same of national security, like, \’this person is a threat\’ language. That\’s what it looks like. This is somebody who has a family, who\’s been in Georgia for 10, 12 years, I think.

It\’s unclear to Prado whether or not the man has an attorney working on his immigration case. Further, this man\’s case isn\’t an isolated incident in ICDC. Multiple detainees in Irwin are often brought in and given little to no communication or insight into their situations, much less resources for getting out.

“We have inmates in Irwin that have not seen their deportation officer in eight months,” explains Carrillo. “Literally, they come in, they sign a book, and they have no answers. Zero answers about their cases.”

Early last month, five men were transferred to ICDC from another ICE facility in Georgia. Upon arriving at ICDC, they were placed in the same cell where they quarantined together for 14 days. One of the men exhibited symptoms of COVID-19, such as trouble breathing, a swollen throat, loss of appetite, and body aches. He submitted two medical requests to ICDC staff. The facility did not provide the men with masks, gloves, or any sanitizing materials in preparation for the outbreak or in response to it.

According to Hamilton\’s press statement, the man has submitted five medical requests on the sick detainee’s behalf in addition to the original two, making a total of seven requests. Other detainees in the cell reportedly banged on the door, “pleading for ICDC staff to remove the sick man and test him for COVID-19.” The staff “brushed” their concerns asied, claiming the man only had “allergies.” Additionally, staff did not respond to the medical requests for almost a week. When personnel eventually brought him to the facility’s medical station, they gave him little more than aspirin and amoxicillin, an antibiotic. The man was then returned to the cell to finish the 14-day quarantine.

After being stuck in a cell together for 14 days, the five men were moved to the general population area of the facility, where they were mixed with over 20 other men. The first week of February 2021, the man exhibiting symptoms was tested for COVID-19 by ICDC staff before he was scheduled to be deported, which is required by ICE protocol. When he did not return to the housing unit after being tested, other men in the unit became fearful that he “indeed had the virus, and spread it to the others,” according to Hamilton’s official statement.

Another man in the cell said in a Skype interview with Hamilton last Thursday that he became very concerned about his well-being. Having asthma and being in his 50s, he is at especially higher risk of severe illness if exposed to the COVID-19, a virus that primarily attacks the respiratory system. He relies on an albuterol inhaler to manage his asthma, but as of Feb. 11, he stated that he had not had an inhaler for five days because the ICDC staff refused to provide him with a refill, “belittling his and other detainees’ requests for medical attention during the most severe public health crisis in recent history.”

The asthma-affected detainee, who stated he has suffered from asthma his whole life, also reported that when he asked for an inhaler refill from the nurse, they said, “Why are you using it so much?” This is one example of medical gaslighting in which medical practitioners deny a person’s illness or condition entirely.

“On the outside, I use my inhaler only twice a day, but it’s bad in here,” he said. “I use it maybe 14 times a day [in ICDC] because this place is messed up and dirty. I know my asthma. I have been managing it for 52 years.”

On Feb. 12, another detainee reported to organizers that the man with asthma was called to the medical center, despite not having submitted a medical request for himself and not experiencing any COVID-19 symptoms. An ICDC official later entered the housing unit in “full personal protection equipment (PPE), including a disposable smock, two face masks, and a face shield.” The official instructed men in the unit to pack up the asthmatic detainee’s belongings. When the men refused due to fear of contracting the virus, the official told the men, “I don’t blame you.”

One detainee who reported these events to organizers said in their phone interview with Hamilton, “Her suggestion to have us clean the room demonstrates apathy on a moral and professional level.” He also shared with organizers he has high blood pressure, which categorizes him as high-risk for contracting COVID.

“Our backs are against the wall,” he said. “We’re just watching each other fall from coronavirus.”

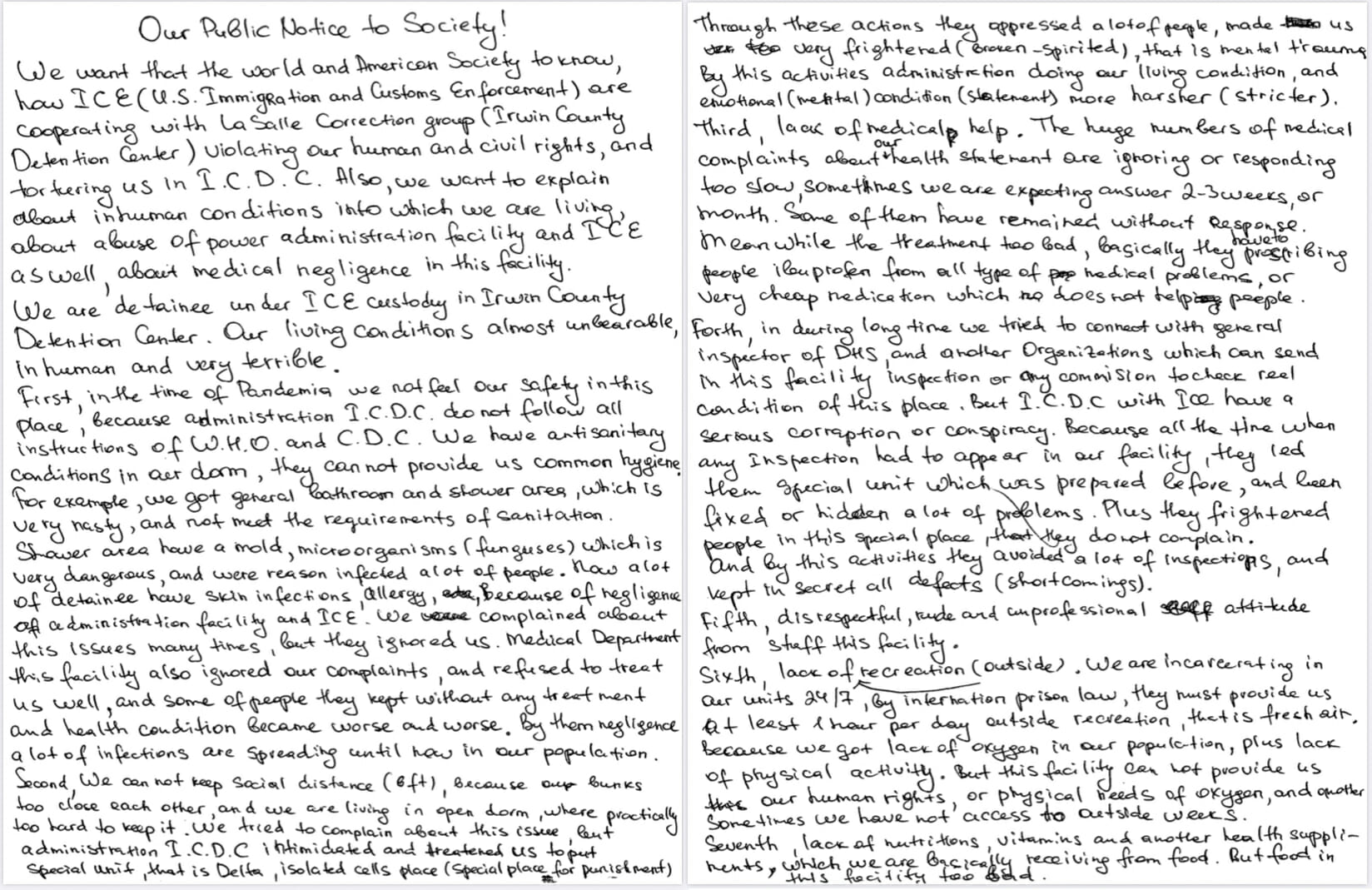

Detainees in the facility have submitted at least five letters to organizers and lawyers speaking out about unsafe health conditions in ICDC and seeking help. These letters have now been obtained and reviewed by The Mainline and are pending full publication. In these letters, detainees have expressed they fear for their lives because “ICDC is not adequately protecting them from the COVID-19 pandemic.” One of the letters states, “ICE is continuously bringing new people into the facility, mixing us all together without following COVID-19 guidelines. There is no social distancing, no regular testing, and guards are visiting the dorms without masks.”

Another letter says, “It is a matter of ‘when,’ rather than ‘if’ our pod will be infected by the virus.”

The hostile and unsanitary living conditions in the facility are not new in light of the coronavirus pandemic. Another letter, written in Spanish, has 25 signatories and includes the date each individual arrived at Irwin. Some detainees who signed the letter have been at ICDC since 2016 and 2017.

The statement includes English-translated sections of the letter, which says, “The living areas only have two bathrooms and two showers, each for 50 to 70 people … the showers are not maintained hygienically, for example the ceilings are covered in mold (sic).” The detainees continue, saying, “The ICE officials constantly treat us like people of the lowest rank, often with sarcastic and racist comments; also, they only come once a week and they are often annoyed when we ask them for information about our cases.”

Another letter entitled an “emergency call for help,” citing references to sexual abuse, neglect, violation of constitutional rights, and abuse of authority, says, “We the detainees are writing this complaint to let everyone know what we are all going through in this facility on a daily basis. The way ICE and LaSalle company treats us is inhumane. Majority of us being held up in this facility is due to simple misdemeanors and minor violations that can be dealt with in civil court. We are not a danger to society and thus we should be treated like human beings.”

The letter goes on to more specifically describe the facility’s violations of COVID-19 precautions, saying, “We are being locked down in small crowded dorms with 23-27 people, with limited opportunity for proper exercise, ventilation, and entertainment. This has taken a toll on our cognitive ability and hence leading to anxiety, depression, and in some cases suicidal thoughts/attempts.” The authors of the letter share that most detainees are traumatized and many have suffered high blood pressure (hypertension), minor chest pains, partial strokes, heart attacks, asthma and liver diseases, kidney and liver diseases, mental illness, depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and major allergies that causes hives on the skin.

“But still, we are left in this custody and neglected on many levels,” they write.

Another letter entitled “Our Public Notice to Society!” says, “We want the world and American society to know how ICE are cooperating with LaSalle Correction group (Irwin County Detention Center) violating our human and civil rights, and torturing us in I.C.D.C. Also, we want to explain about inhuman conditions into which we are living, about abuse of power administration facility and ICE as well, about medical negligence in this facility. We are detainees under ICE custody in Irwin County Detention Center. Our living conditions almost unbearable, inhuman, and very terrible (sic).”

All letters describe the same levels of mistreatment, abuse, and neglect of those being detained in the facility throughout the pandemic, although these practices were not absent in our pre-COVID world. Just as the mistreatment of detainees wasn’t any less severe prior to the pandemic, neither was the facility’s unsanitary conditions which simply paved the path for such catastrophic medical issues that are so regularly hidden from the general public and detainees themselves.

“The history of the health conditions and treatment of detainees in Irwin connects with this current crisis,” says Cade. “These are tight congregate settings in which the risk of transmission of something like COVID-19 is very, very high. That’s true at detention centers throughout the country. In this particular detention center, [they] didn’t even have adequate hand sanitizer and other ways to take basic mitigating precautions against catching coronavirus. [Detainees] made their own masks out of underwear. They engaged in a peaceful hunger strike that was published to YouTube and then resulted in pretty extreme retaliation, including a lot of separation of the alleged leaders of the hunger strike. That’s continued to the present day. Even though there may be some masks there, there’s still this situation where people are tightly packed together; and many of whom are at very high risk for not just contracting COVID-19, but for potentially lethal outcomes if they do contract [the virus].”

Following Wooten’s whistleblower account of medical and gynecological abuses at ICDC, a number of organizations and offices came together to advocate for the release of detainees in such unsafe and inhumane conditions. In November 2020, there were over 75 women in ICDC custody and many of them were released through requests filed via Fraihat v. ICE, a nationwide class action lawsuit that was filed in California on Aug. 19, 2019. This is a legal mechanism, pursuant to a federal court order, that requires ICE to release individuals from detention who are at high risk of severe health outcomes if they contract COVID-19.

When asked how many detainees have lost their lives due to COVID-19, Cade referred to ICE’s official statistics, saying that four people have died because of COVID-19 at Stewart Detention Center. There are no reports that anyone at ICDC has died. Further, the statistics only report five current cases and a total of 70 confirmed cases in ICDC. There are currently five women and 200 men being detained in the detention center down in Ocilla, Ga. However, considering that the detention center does not regularly test its detainees, it feels difficult to trust the data provided.

“It’s got to be so much higher than that,” says Cade.

The organizations involved in what is referred to as the “Fraihat release project” include Southeast Immigrant Rights Network; Innovation Law Lab; Southern Poverty Law Center; Sur Legal Collaborative; Immigration Defense Unit, City of Atlanta Office of the Public Defender; Community Health Law Partnership Clinic, University of Georgia School of Law; Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, Columbia Law School; Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, Harvard Law School; Immigrant Rights Clinic, Texas A&M School of Law; and Immigrants’ Rights and Human Trafficking Program, Boston University School of Law.

These organizations and offices are urging ICE and ICDC officials to release everyone currently in detention. They say the recent fatalities of individuals detained in Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., which is run by private corporation CoreCivic and contracted by ICE, make clear that “everyone in detention is at risk of severe illness or death, regardless of any preexisting health condition or age.”

“Alternatively,” the statement says, “we urge officials to release all those individuals considered ‘high risk’ and to regularly test everyone in detention for COVID-19. We also call upon the Biden-Harris administration to take swift action to prevent further deaths among individuals in ICE’s care.”