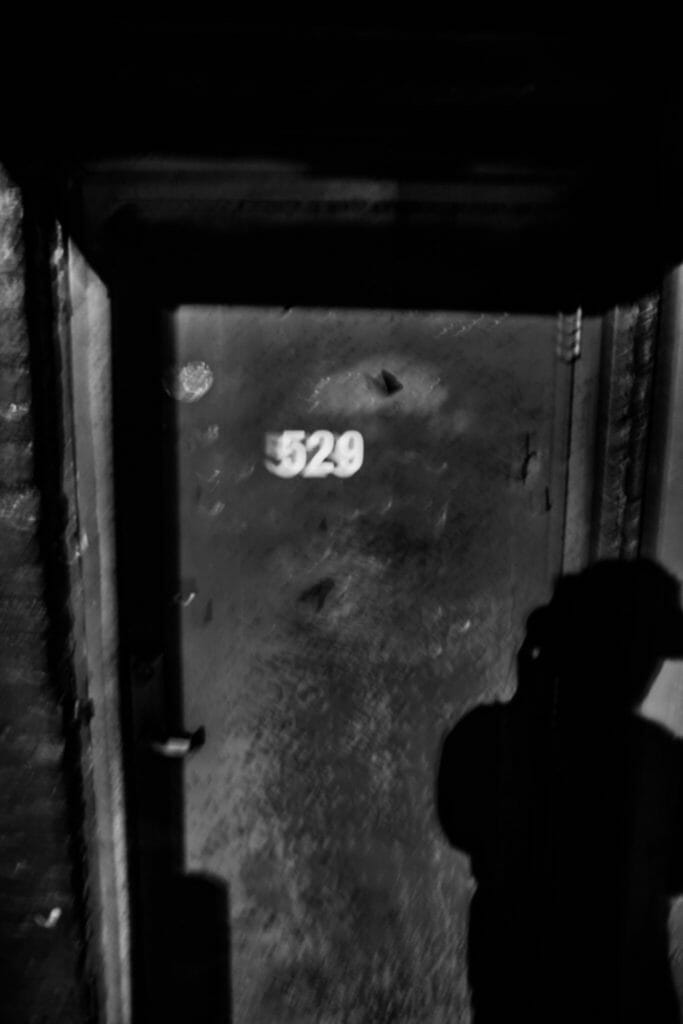

Rev. Keyanna Jones in Atlanta, Ga. Photo credit: Ethan Payne/Scalawag.

This story was originally published by Scalawag as a part of A Week of Writing: Stop Cop City.

This essay discusses state-sanctioned murder and gun violence.

“For if they do this when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?”

— Luke 23:31

In a meditation group for pregnant women, Belkis Teran, Manuel Teran’s mother, felt her body brim with energy, “from my knees to my chin.” A group leader took notice. “It’s amazing—the energy of your child,” he said to Belkis. “I can see that [Manuel] has a powerful light.”

Manuel was born April 23, 1996, and over time, Belkis watched them grow into a person “like bright sunshine.”

Manuel always felt called to help others, with an eye to the future. This work led them to Intrenchment Creek Park, redubbed “Weelaunee People’s Park,” in May 2022. Manuel arrived for a Week of Action, following a call to support the Stop Cop City movement on the ground in Atlanta. They never left. Manuel became a “forest defender,” affectionately called “Tortuguita” or “Tort.” Forest defenders like Tort lived in the Weelaunee forest, and protected the trees with their bodies. On the morning of Jan. 18, 2023, Tort meditated in their tent. Law enforcement agencies raided the forest and fired 57 gunshot wounds into their body. Bullet holes pierced both of Tortuguita’s raised palms.

Rev. Keyanna Jones lives in Southeast Atlanta, just two miles from the site of Tort’s murder. She delivered the Palm Sunday sermon at Park Avenue Baptist Church about the fight to Stop Cop City. “They have mainstream media, they got elected officials, they got preachers coming out condemning us, and we feel like it’s so dark,” Keyanna preached. Press initially reported that Tort shot first, while body cam footage suggested gunfire exchanged between officers. The GBI claimed Tort fired a bullet, conflicting with the results of a Dekalb Medical autopsy report, which indicated no gunpowder residue on Tort’s hands. Belkis and her family have yet to receive an independent investigation into Tort’s death. Though the situation is dark, Keyanna encouraged the congregation to water those “seeds of justice” with faith, because “faith is action.”

Belkis is the daughter of a pastor with a license in theology and a master’s in pastoral care and counseling. She is Venezuelan, of Indigenous Timoto-Cuica descent, and raised her children in Panama, where Tort became active in their community—feeding people, caring for elders, and cleaning beaches. Teenage Tort told Belkis, “Mami, I don’t do anything sitting in a church.” Tort was compelled to join the Stop Cop City Movement from Florida, where they built houses for low-income Hurricane Ian survivors.

Weelaunee People’s Park included unhoused people who were fed and sheltered through the movement. Tort coordinated “Brown Cat Mutual Aid,” distributing resources to forest defenders and marginalized people in the wider community. Tort “was doing Jesus’s job and was killed for that,” Belkis said.

The Tuesday before her Palm Sunday sermon, Keyanna stood up at the Stop Cop City Community Town Hall, held inside Park Avenue Baptist Church on March 28. “We ain’t in no church belonging to the so-called Concerned Black Clergy (CBC) who continue to take your tithes and sell you out to the APF (Atlanta Police Foundation),” she said, to thunderous stomping and applause. She called out members of the Concerned Black Clergy for their silence during the construction of the police training facility. “If your pastor is not willing to have a conversation with you about Cop City, then you need to leave and stop paying tithes immediately,” Keyanna said. “You’re funding your own oppression.” That same week, clearcutting began in her neighborhood—the place where Keyanna grew up and now raises a family.

Keyanna understands Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” as a rallying cry to clergy people. “Clergy members back then were concerned about … the repercussions of their involvement,” she said. From Keyanna’s perspective, such concern should not be “the charge of the Black church in Atlanta today.” Keyanna, a clergy member and activist, is concerned with social justice. She organizes with Community Movement Builders, fighting for poor and working class Black Atlantans to end police violence. Keyanna joined the movement to Stop Cop City when Andre Dickens supported the training facility in his 2021 bid for mayor. The CBC, closely tied to the Atlanta police department and mayor’s office, came out in favor of the facility in March 2023.

On March 5, 2023, 23 people were arrested and charged with domestic terrorism at a music festival for a Week of Action. Police stormed the festival after protestors burned equipment at the training facility and threw fireworks at officers, according to officials. News reports emphasized that only two of the people arrested were from Georgia. Festival attendees observed that officers released people with local addresses to further the outside agitator narrative. In Dr. King’s Birmingham letter, he wrote, “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea.” Keyanna took action against the outsider narrative, as part of the “Faith Coalition of Forest Defenders,” an interfaith leadership group. She moderated the coalition’s press conference on March 6.

Reporters asked why a majority of people engaging in violence came from other states and countries, and Keyanna answered, “The ones who are engaging in violence are the police. And they’re from right here in Atlanta, Georgia.” Faith leaders across traditions stood in solidarity as Rev. Leo Seyij Allen, a Baptist minister and fellow member of the Faith Coalition, read the group’s letter aloud to city council. The letter decried the destruction of the nation’s largest urban forest, Atlanta leadership’s alignment with corporate interest, and investment in the militarization of police. They called for a complete stop to the Cop City Project and an independent investigation into Tortuguita’s death. They also demanded that all domestic terrorism charges against protestors be dropped. On March 10, the CBC held their own press conference.

President Shanan E. Jones and other well-known Black clergymen spoke to the press in front of Atlanta City Hall. “In this city, the spiritual home of MLK Jr., we are not going to allow you to destroy our rich legacy of protest,” Shanan said. He asserted, “We think that the center should be built,” and that “folks who throw Molotov cocktails at police” are domestic terrorists. Rev. Gerald Durley also condemned the protesters’ destruction of property. “Violence is not the answer,” he said. The CBC did not mention the violent history of the training facility’s land, or that it was stolen from the Mvskoke people and made into a prison farm. There was no mention of police violence against Black and brown people’s bodies. Manuel’s name was not spoken once.

“If people are to truly be free, they have to first believe that they will be free.”

— Rev. Keyanna Jones

Pastor LC Wheat came to the weekly Concerned Black Clergy Community Forum with a mission. He counted nine funerals he’s led for youths killed by gun violence this year, and 36 last year. Wheat is one of the faith leaders spearheading a mission called Operation P.U.S.H. Too, or Praying Under Severe Hard Times. Their group, which focuses on preventing gun violence among youth, plans an upcoming “Jam For Peace,” a day of “peace, love, family fun and live entertainment.” He asked everyone to come out at the community forum. Wheat believes a pastor’s role is to “speak truth” and “bring light,” to issues like gun violence—issues that create anger and hatred. At funerals for these youth he said he often quotes Hosea 4:6: “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.”

Rev. Allen was raised in the Black Baptist church. “It’s in my blood,” they said. “I love the culture … as well as the history.” They once saw Cop City as an inevitability. They consider their decision to join the movement “a moment of [their] own faith being challenged and tested.” Allen attended a meeting of the Coalition, and they were “immediately drawn in” by the members’ defense of the defenseless, the forest, and fight for all people. Allen’s work draws from a Black Baptist history of liberation and empowerment “in opposition to hierarchy and oppression.” A queer, trans Baptist themself, Allen asserts their place in ministry and asks, “What does organizing in the Black church look like today?”

Pastor Wheat’s crusade against gun violence is close to home. His nephew, Caine Rogers, was shot and killed by a police officer in 2016 at the age of 22. Rodgers’ killing led to the Justice for Caine Foundation as well as the indictment of Officer James Burns for his murder. “We want all these officers to be held accountable,” Wheat said. Wheat is an Atlanta native, and his mother lives just two blocks from Cop City. The full impact of the $90 million project remains unclear, though his mother has lived in the area for thirty years. “How can we support something that we have no knowledge of?” Wheat asked. “If the city gon’ do this … without our say-so, at least tell us what we are embarking upon.”

In September 2021, despite upwards of 17 hours of public comment against it, The Atlanta City Council voted 10-4 to authorize the Cop City lease. The Sierra Club of Georgia released a response penned by Chapter Executive Committee Chair and 2007 CBC “Young Man of the Year” Daniel Blackman. “Instead of listening to the will of its citizens, the City Council voted under the cover of darkness,” he wrote. Blackman, who works as the Administrator for EPA’s Southeast Region, has not since commented on the construction that destroys the South River Forest, known as a “lung” of Atlanta. Construction continues, despite a now-lifted stop work order, as well as resignations and a Limited Denial of Participation appeal made by members of the project’s advisory committee, which was appointed by the mayor’s office. The appeal cited a violation of Atlanta’s land ordinances and Clean Water Act. The appeal was denied.

Shanan is sure that “Cop City’s gonna come.” When asked about the need for police, he recounted the recent mass shooting at a Christian school in Nashville. He watched “officers neutralize that woman. That was training … we need a place to train.” He is disturbed by America’s “fixation on guns,” a cause the CBC organize around as “Clergy With a Candle,” an awareness-raising effort against “citizen to citizen violence.” Shanan condemns “violent” protest at the training facility, 8 miles from where Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King are buried. “That’s not the way that we’ve overcome as a people, Black people didn’t pick up Molotov cocktails,” he said. A former pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, Shanan supports protest that is “Kingian.”

“If you’re not talking about police brutality, then don’t talk about Martin Luther King Jr,” Baptist Minister and Faith Coalition member Matthew Johnson said. Quoting Dr. King to quell dissent, he said, is “asymmetrical.” Without organizing around systemic causes of gun violence, like unemployment, hunger, and homelessness, Johnson claimed, the CBC’s activism is “reactionary.” A Morehouse graduate and Atlanta resident, Johnson likens the CBC to pastors of well-known churches who “deserted” Dr. King when his message threatened their financial, or political security. Their public support of Cop City demonstrated “a lack of prophetic imagination applied to healing the world,” Johnson said. Founder of “Beloved Community Ministries,” Johnson’s vision is a “Beloved Commune” for Black and Indigenous activists, free of policing.

Allen now sees “the glimpse of that alternative vision,” without policing, but rather, one of “community care and self governance.” They follow in the tradition of ancestors like Prathea Hall and Fannie Lou Hamer, who according to Allen, “push the Black church to be a beacon of hope when it comes to human rights and civil rights.” Allen took to the microphone at the press conference, to read the faith coalition’s letter, signed by hundreds of religious leaders. “Good afternoon,”they greeted, and the crowd murmured a weak response. “C’mon y’all, I’m Baptist, so you need to talk to me.” Upon listing the demands of the letter, Allen said, “We are not the ones asking or demanding this … Friends, this is God’s plan for Beloved Community.”

“For, in fact, the kingdom of God is among you.”

— Luke 17:21

The Stop Cop City weekly food pantry and potluck congregated on the corner, mere feet from Weelaunee Peoples Park. The park was closed by Dekalb County because of “traps” officers found in a raid; they destroyed the altar erected to Tort’s memory. Cement blockades were placed at the entrance. Prohibited from entering the park, the food pantry persists week after week. Friends embraced each other over a shared meal. Neighbors’ cars stopped for free groceries. People painted and played the guitar, while police surveilled from the barricades. Scrap wood and tools were collected to build a new memorial to Tort. As the pantry ended, people knelt before the simple altar, silent before the painted words, “Viva Tort,” “Tort Lives.”

Acts 2:47 reads, “All the believers … had everything in common … they ate together with glad and sincere hearts.” Johnson’s “Beloved Commune” is inspired by this Bible verse. He combats that “deep abiding sense of scarcity within us” with “the gospel of Jesus Christ.” On April 23, Johnson celebrated what would have been Tort’s 27th birthday at Park Avenue Baptist, with a service featuring Pastor Darci Jaret’s painting of a turtle. Rev. Allen invited the congregation, including Belkis, up to the altar for “an active moment of response,” to spread handfuls of soil along the ridges of the turtle shell. Spreading dirt, Allen said, is a commitment to the belief that “another world is possible.” The congregation covered the turtle shell, and Johnson embraced Tort’s family with tears in his eyes.

Pastor Jaret delivered the “Earth” segment of a four-part “elemental” sermon for the Easter Sunday service. “Teach us the Sacred Web of Abundance that flows outward from the land, the story of Jesus rising from the earth,” they preached. The Sacred Web of Abundance (SwoA) is an idea from the Weelaunee Web Collective, that liberation comes from our connections to each other and the land, honoring Indigenous stewardship. The Mvskoke people in Georgia and Atlanta are the original threads in the SwoA that autonomous communities, like Weelaunee, must connect to. Jaret’s prayer to the Weelaunee Forest, as a member of the Faith Coalition, imagined “a bed of pine straw,” being enough to “slow down the waves of oppression.”

Creative imagination is a key aspect of Park Avenue’s abolition. Like most Christian thought, Jaret sees abolition as “a concept that lives in the imaginal realm of possibilities.” Jesus’s life and death represented possibility for the world. That Jesus died for our sins, the pastor said, is “shallow theology.” They consider Jesus’s resurrection in the “imaginal realm,” representing what could happen “when we really free each other.” Rev. Nolan Huber-Rhoades is a parishioner at Park Avenue and a documentarian capturing the movement. He believes Jesus was executed for threatening an imperialist system, not unlike the United States “empire” today. “This movement to Stop Cop City is a spiritual movement,” he said, and Tort’s spirit, “is living on through this movement, in a very Christ-like way.”

Early Easter morning, birds sang and white-tailed deer foraged. A bulldozed path, lined by felled trees, led to the remnants of Tort’s altar. A turtle shell lay halfway visible in the mud, buried, yet unbroken. Belkis prays for Weelaunee, for the people who are carrying the torch of Tort’s legacy, “giving love to everybody, giving food to the people.” At the potluck, activist Jesse Pratt Lopez read her poem before the rebuilt altar. “In the face of perpetual violence to land … we sang and ate and danced again.”

Belkis prays for the strength of the community. She prays in silence, to feel Tort’s presence. This brings her peace. She knows her child is still alive, she said, “by faith.”

Zoey Laird is an Atlanta native from an Episcopalian family. She’s spent years asking questions about Christian religion, and is most intrigued by worship spaces and images of the virgin mother. She’s worked for radio broadcasting, including npr station kdlg 670. She’s motivated by collaborative making, most recently a zine called ANI: Atlanta narrative imagination. Check it out @ani.time.atl

Scalawag is a journalism and storytelling organization that works in solidarity with oppressed communities in the South to disrupt and shift the narratives that keep power and wealth in the hands of the few. Read more stories from Atlanta organizers featured in Scalawag’s A Week of Writing: Stop Cop City.

Contribute to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund to support the legal defense of Forest Defenders facing domestic terrorism charges, and learn more about the ongoing fight to #StopCopCity and defend the Atlanta forest.