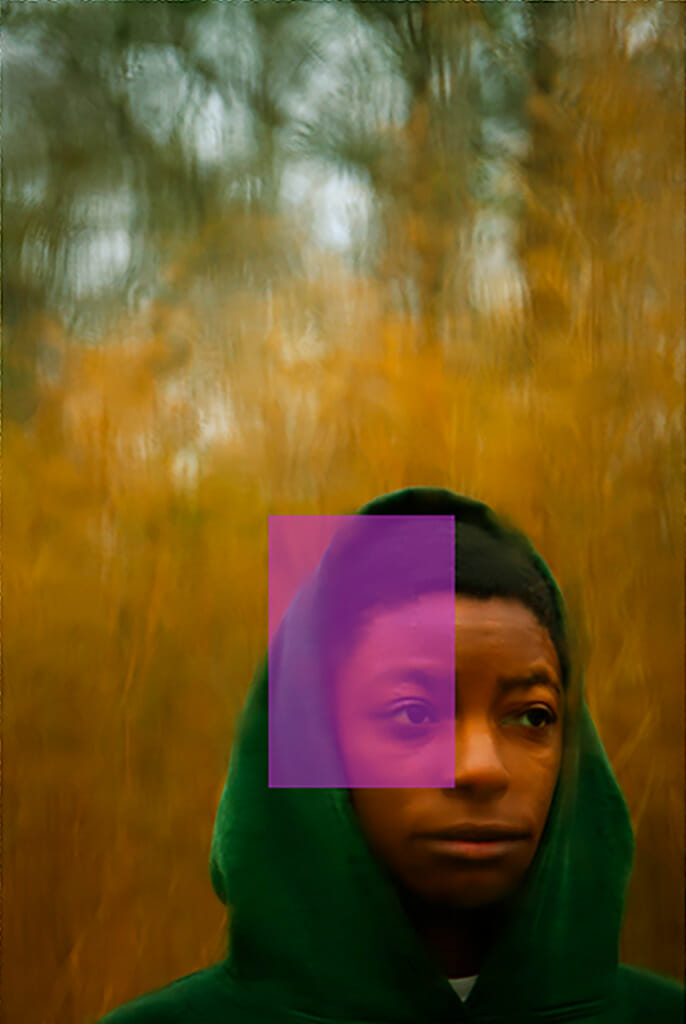

Originally published in The Boundary Issue on March 22, 2020. Taves\’ Akátá EP is out now via Harsh Riddims.

“Think about how you respond to Black hair and what the fuck you’re saying when you think about Black hair, because a lot of that shit is conditioned. I don’t even know how to fucking feel about it anymore… except to make my ass easily accessible for haters to kiss it.”

These are the words of house/electronic musician Taves, 25, from their live performance at the Mainline/Irrelevant Music/My Illegal Body event in September 2019 in Atlanta, Ga. They were wearing a crop top, a mini, and a blue wig, dispersing some quick jabs of real talk in between the beatific drone tracks that comprised their set. When I went to find more of Taves’ music online, I didn’t find much outside of a SoundCloud account (tavesfaves) that featured a few demos dating back to early 2018. No Facebook, no “About” page, no Instagram, as far as I could tell. But there’s a reason why Taves isn’t really to be found on the internet; perhaps this isn’t the type of “accessibility” they were referring to.

Those demos are now the Akátá EP that is to be released at the end of April 2020 via Harsh Riddims (Ryan Park/Fit of Body’s independent Atlanta-based label). In the beginning of our interview, Taves explained that “Akátá” means a “cat away from home” in Yoruba and doubles as a pejorative for Black Americans who were enslaved. Needless to say, I knew what Taves and I would be talking about for almost the rest of the interview. Read below to learn Taves’ story, why they are wary about sharing themselves online, and what it means to be POC in America (and more specifically, Atlanta) today. Like, what it actually means. Not what people who claim they’re progressive think it means.

The demos for Akátá go back to around February 2018. Can you share with us about your process, the recording, and what it’s been like for this one?

Usually when I start writing music, it’s either out of boredom, anxiety, frustration, or all three. So that was where that came from. I actually made that project with not releasing it in mind, so that’s probably why it took me two years to release it. As far as my process, I use Ableton, I build my own beats, I build my own parts, everything I produce myself. Except for the official tracks, [which] a friend post-produced … But for the most part, I created everything myself. I’m trying to think about the process, it was so long ago (laughs).

I’m interested in the boredom, frustration, anxiety — do you feel that’s where a lot of your work comes from? Can you tell me more about that?

The frustration is the main thing for me, because I feel like it’s difficult to communicate with the outside world in just plain speaking and conversations. So I gravitated more towards music, because it was hard to say certain things without people either getting up in arms, like offended about it, or just like tired of hearing the same rhetoric. My frustration is deeply rooted in my depression from both being a physical issue as well as a socio-economic issue. Because of my family background, most of the time it’s been very dysfunctional. And that caused me to have a hard time in opening up and talking to people and properly [expressing] myself. So I felt like music was the only proper way I could express myself without stepping on toes.

It sounds like your music practice is pretty private and is more for you to cope with things — the human condition. Is that why there’s not a lot of online content?

Yeah, I don’t like the idea of being consumed, because I feel like that’s the end-all-be-all for most Black people in America: to be consumed. It’s so attached to social media for me, where I have a strong protest and disdain for [it]. I don’t use it or I disable it a lot. It’s a huge way to compartmentalize a person of color, especially since we have this racial polarity here. It happens to be the black skin mostly when it comes to cultural trendsetting. Like, it has been based and built off of Black bodies. The whole thing about people liking Black culture but not Black people is that kind of started, for me, in my opinion, the whole perspective of covert racism. You know, I know many people who are like, “I love this artist who’s Black” or “I love this author who’s Black,” but in their day-to-day lives, I can see micro-aggressions they perpetuate. I also see ways where the conversations go over their heads. And I’m like, are you actually trying to understand the more human part of Blackness, or are you more attracted to the superficiality of it? Like what you see, and what you feel from it whenever you see these elements of Blackness and edginess and creativity driven from poverty. You know, those kinds of things, and a lot of white people — especially within my circle, artists around here — who are not making the full connections about how that doesn’t necessarily constitute as understanding Blackness and the struggle of being Black.

Do you have any examples of that, where the connection isn’t coming all the way through?

It usually has a lot to do with the socio-economic part of it. I have a lot of friends who mean very well, but we’re from different classes altogether. And it’s like, yeah, we’re middle class. We share that in common. But at the same time, I’m more so lower than middle-class, and I have friends who are middle to upper-middle class. And whenever I talk about things like school, like, “It’s too much to go to school,” and they’ll be like, “Yeah, I understand, the mental effect and emotional aspect of not being able to go back to school.” And I’m like, I was talking about money. Then going into certain spaces with my friends who are either lighter than me, or a completely different race, or white all together where I am approached last, I’m addressed last, and people don’t even notice that. And I notice it every single time. That’s my reality every single day. That’s some people’s reality every single day.

What do you think the local music and art community can do better? What should it continue doing?

As far as right now, what’s going well, I’m starting to see more people of color on bills that I otherwise wouldn’t see. A lot of alternative bills, or indie rock bills, or DJing, even. Because I noticed that was really white for a second, and a lot of Black DJs weren’t getting as much face time or as much work because they didn’t have the same platforms or that much money. But that’s starting to change now with the DIY spaces that are putting on Black artists and then the Black artists themselves, the DJs, are creating their own platforms. As far as how it can be better, I would like to see people really push what they believe a Black body can be seen doing. So I would like to see a lot more acts where it’s very unconventional, it’s not in the lane of trap, or R&B, or something that’s known for being a Black-based genre or lane. It would be nice to see Black artists but in the same space and held at the same respect as the white artists.

Are you tapped into politics right now?

I kind of am, but at the same time, I’m not super well-versed. A lot of my political understanding comes from my day-to-day life and how I walk through the world. ’Cause I come from an area where there are little to no white people there. So it’s like, being in that kind of setting… I’m like, in my area with all these different backgrounds within a close proximity — you know, if you’re a compassionate person — there’s different obstacles and discrimination that other groups go through, and just becoming aware of that. So that’s how I’ve been informed politically. I would be in class with a friend, and we were all getting ready to go to college. And one of my friends was like, “Oh, I can’t apply because I’m not a citizen here.” That whole dream for her was stripped away because of that one fact. Being 16 at the time, you’re just like, “What the fuck? Why is that happening to you? You don’t deserve that.” And all these other thoughts that start pouring out. As far as my friends who are part of the Asian community… a lot of my friends are from Vietnam. And learning about the conflict of the Vietnam War and the residual effects of it, on the families’ mental health, on how they operate financially, on how they move through the world, and how they present themselves because of this conflict from the ’70s, it’s just something that spoke to me. And it’s just like, that’s crazy. It’s like how I still see the effects of slavery in my household.

How can visual art and social media be navigated differently for Black artists to feel and be more respected rather than consumed?

In a lot of ways, I kind of just refrain from most visual media. I feel like a part of me is retained and preserved by doing that, by not participating in that aspect. As far as music videos and video interviews and things of that sort, I can’t do it. Because I feel like once you see the visual of a Black artist, that becomes the only thing people can focus on.

So did Ryan put you up to putting out the Akátá EP or did you reach out to him?

It was a personal decision. I reached out to him. Because I have seen his work and his performances and what he’s doing in the Atlanta music community, and I was like, “Yeah, I’m gonna work with this person.” This is the most genuine label I’ve seen, and this is also the most genuine attitude, because a lot of people get caught up in branding and aesthetics and appealing to a certain group of people. And he does have that element to his work and everything, but at the same time, it’s like, it felt like a home, you know? Like this is where you can come as a Black artist and you don’t have to worry about being confined into boxes.

What are your influences for this EP?

As far as influences in music, it stems from all Black music, period. Even going into the UK. A lot of the UK has influenced my music: two-step, their house [genre] over there, garage, just the way they do music over there. And seeing a lot of Black artists that we hadn’t seen here because we live in a huger country, it’s not as concentrated as there. And a lot of the artists there are talking about how Black people are seen. We want to be able to celebrate, we want to be able to live, we want to be able to express our pain, but just leaving it out on the dance floor. And that’s something that really spoke to me, especially Chicago house here. Just letting everything ooze out in beats and melodies and calling and responding to certain lines in music. A lot of Black artists created those kinds of elements, so you could be able to have a fabric whenever you’re in a room with other Black people. And I’ve seen that that’s started to kind of dwindle a little. Like especially [in Atlanta] with Trap. Like, for me, I do enjoy trap music, but as far as the community, I’m not very attached to it, I’m not very connected to it. But at the same time, I can admire it. But also at the same time, I want to be able to create a new space where Black people who don’t feel like they fit in that paradigm can come be like, “Alright, this works. I can be as strange and weird and responsive and reactive as I want to be.”