Some basic information about the right to demonstrate and tips about navigating police harassment

Author’s note: This article contains information received during the “Know Your Rights for Mediamakers” seminar hosted by local documentary filmmaker Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz, with panelists Ría Thompson-Washington and Katie Steinberg. Thompson-Washington is a legal worker who’s worked with the National Lawyers Guild for the past six years; she’s also worked at the New Georgia Project throughout 2020. Steinberg is the Mass Defense Chair of the Washington, D.C., chapter of the National Lawyers Guild, where she leads 600+ lawyers, law students, and legal workers for the Legal Observer Program. Ebrahimi Bazaz also received programming and outreach support from the AMPLIFY collective, which is a group of organizers, scholars, filmmakers, and educators working to leverage media-making as a tool for advocacy, protest, reflection, healing, and community building.

ATLANTA — In light of the recent FBI raids and protest arrests that have taken place in Atlanta the past two weeks, it has become clear that state repression of activists — especially Black activists — is no longer something we can claim as history or theory.

As there has been minimal reporting around state repression of civil rights activists across the country, we have yet to determine if this is unique to Atlanta. However, Atlanta is unique in that it leads the U.S. in camera surveillance, and its local government infrastructure has proven it is not a place to foster movements as so many like to wistfully recall from the 1960s era.

As civil unrest is expected to continue throughout the rest of 2020 and beyond, it is imperative that those participating in civic engagement, whether that be on social media, on-the-ground demonstrations, or otherwise, understand their rights before, during, and after demonstrations in regards to their interactions with police and law enforcement. It is vital to protect the act of protest and demonstrations to be sure it can withstand repression from the state, which can occur by means of destroying social movements through intimidation, arrests, and draining them of resources.

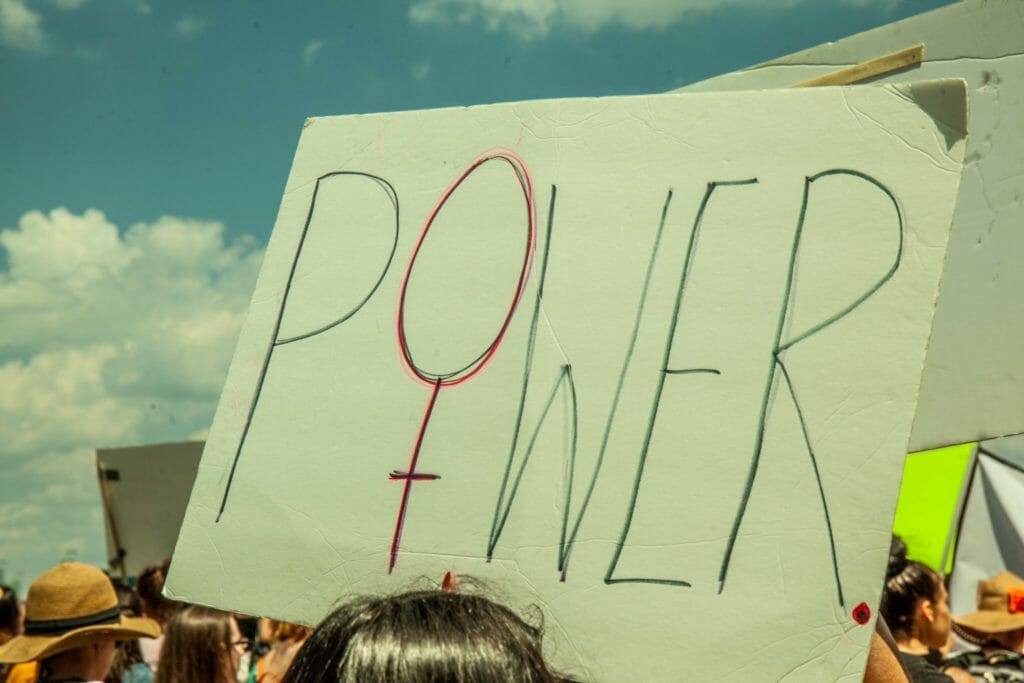

Protests occur when the government has all the power, people need to reclaim it, and the only tools available to make change are through collective action. However, one’s personal power is highly curtailed by their circumstances and how they show up to the state in terms of their intersectional vulnerabilities (nonbinary, undocumented, Black, Indigineous people, people of color, women, trans — basically anyone who isn’t a white cis male). To be clear, solidarity is the best way of protecting others, especially the vulnerable, from state repression on and off the ground.

This article contains specific information surrounding rights to demonstrate along with tips about navigating police interaction, with special considerations for marginalized groups such as undocumented, trans, queer, and BIPOC citizens. For the purposes of this article and publication, when we refer to “oppressed groups,” we mean BIPOC, women, trans, and queer. According to Thompson-Washington, “Oppressed people face the reality of state violence much more harmfully … and who you are determines your interaction with police.”

The First Amendment

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a dress of grievances.”

While the First Amendment, as it is written, seems like it covers just about everything when it comes to freedom of speech, whether that be in the form of the press, protest, or in public spheres (in these times, social media), there are certain parameters surrounding the right to free speech many may not be aware of.

Higher courts have curtailed the first amendment in a number of ways, including in content-based restrictions which “include not only restrictions on particular viewpoints, but also prohibitions on public discussions of an entire topic.” Moreover, the ongoing, unfair extradition trial of Julian Assange presents even more dangers to press and publishers’ right to free speech. Further, police will violate your right if they think the need to suppress outweighs your right to free speech and free press. The bottom line is, the First Amendment will not protect individuals in a police encounter; the amendment comes in after the fact in a line of defense in a court of law.

We also recommend that people look to history to determine who the state favors versus who they don’t. We can easily look to examples of MAGA protests that took place earlier this year in which police gently handled enraged and armed white protesters compared to how they collectively address civil rights protesters in the Movement for Black Lives. In this climate, it appears not only do certain intersections of vulnerability affect individuals’ interactions with the law, but political and ideological views do, too.

The following contains important information, which may reaffirm common knowledge and debunk widespread ideas that surround police and basic constitutional rights.

Three levels of interacting with police

Contrary to what may be popular belief, police are by no means required to tell you they are police. Police officers are trained and empowered to lie, which means they have what it takes and are even taught how to utilize their position and skills to fool citizens into unknowingly turning over evidence against themselves or others. In regards to individuals interacting with police, anything the person says could be used against them. At all levels of interaction, it is ultimately best to not say anything at all.

There are three levels of interacting with police, and each stage includes “magic words” to keep in mind during these stages. Bear in mind that the “magic words” don’t mean that police will magically respect your rights, but they will help individuals later in court.

Conversation

At this stage, police are interacting with individuals in conversation, casually asking questions or what may even appear to be small talk. It is important to be cautious during these times and it is best to politely, but firmly, refuse to talk or engage. If police ask for your name or documentation, be aware that you don’t have to give information to them — but not giving your name could result in an illegal arrest. The best route is to ask if you’re being detained and if you’re free to go.

Whatever you do, don’t run from the police under any circumstances. A lot of people run because they are triggered, which is understandable. But do not run in a panic from the police, as it will bring reason for arrest and additional charges.

“Magic words” at this stage are: “Are you detaining me? Am I free to go?”

Detention

At this stage, police have reasonable suspicion against you and it means you can not leave. While it is true that they can not hold you longer than it takes to investigate you or confirm their suspicion, in reality this means they can essentially hold you however long they want. This is the moment when your right to attorney and right to remain silent become amenable, and is why police will try to stay in the conversation stage as long as they can in order to obtain “consensually given” information from subjects.

At this stage, they are free to search and pat you to determine if you have weapons. You can exercise your right to not have a search, but they don’t have to respect your wishes. As uncomfortable as it may be, don’t try to resist the officers searching as it can lead to additional charges.

“Magic words” at this stage are: “I do not consent to a search.”

Arrest

If you’re arrested, the best thing is to not say anything at all. Be sure to assert that you are going to remain silent and you are going to speak with a lawyer.

“Magic words” at this stage: “I am going to remain silent. I want to see a lawyer.”

Potential charges at protests

There are a number of potential charges one could obtain at a protest. These include, but are not limited to:

- Assault on a police officer. This is a really easy charge in many jurisdictions and can be as simple as not listening to orders. It is important to be aware of different jurisdictions and their laws and regulations.

- Unlawful entry

- Blocking passage

- Crossing a police line

- Failure to obey

- Private home protest

- Federal charges (Congress, National Parks, SCOTUS, White House; there are special charges for arrests at certain locations)

- Conspiracy rioting or inciting to riot. This is new and also known as the J20 Charge.

After the arrest, it’s best to not talk about the conditions of your arrest with anyone at all besides your lawyer. This includes family, friends, and people in your affinity group. It is in yours and others’ best interest to not talk about anything that’s happened while you were on the street, because that creates an opportunity for undercover police or someone else to use that information against you or others.

It is important to remember that you may not have actual access to an attorney until you make it to the court. You can ask to speak to an attorney at the early stages to let police know you’re not going to speak or answer questions, but you’re not likely to speak to an attorney until you see a judge. You may also consider being mindful of what you say to the lawyer at this stage, because they may not be the one representing you in the entire case. Ultimately, it is best to wait until you are with the lawyer who will be representing you throughout the case.

Notes on searches

To further emphasize on searches: you can assert that you don’t consent to a search. However, if the police continue to search anyway, don’t resist, because it can lead to additional charges.

For those in the press, you probably have equipment on you for collecting data for coverage. Since it could be susceptible for searching, whether you consent to it or not, it is up to journalists and reporters at this time to determine what exactly they’re covering and whether or not it’s worth it. (More on that later.)

If a search occurs, even against your consent, be sure to attain the officer’s name and badge number if possible. If they ask for different levels and points of searches casually, do not consent. Officers are likely to do this rather than obtain a warrant in order to obtain evidence they can use against you in court later. In the case of a home search warrant, be sure to investigate the scope for what they’re actually looking for or what the search warrant says they’re there for.

Electronics

As it stands today, the law has not completely caught up with technological advancements in our society, leaving a lot of gray areas as far as what is constitutionally protected and what isn’t. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, an organization that conducts policy and research around electronics, equipment, and footprint, recommend that you password protect your cell phone with at least six characters.

Courts at this time haven’t determined if it’s a violation of fourth amendment rights to use bio-metric data (Face IDs, fingerprints, etc.) to access your phone. Earlier this year, there were reports of police in New York City asking for people to remove their masks in order to open their phones. Currently, phones that are not password protected do not require a warrant.

The Fifth Amendment

“No person … shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.”

It is entirely possibly in many cases that we think we are being entirely lawful and law abiding, when in actuality we are not. There is always the potential for breaking the law without even realizing it. For example, it can be a crime to lie to the police or simply not listen to the police. Further, laws vary in different jurisdictions. You may have the right to demonstrate on the sidewalk, but not on a part of the street.

Remember, police are trained to get confessions out of suspects. Innocent people routinely confess crimes without realizing it. The longer you talk to police, the harder it is to stop, and the more likely you somehow incriminate yourself. Moreover, you can’t talk your way out of getting arrested. The best thing to say, under any circumstances, is “I am invoking my right to remain silent.”

Special considerations for non-citizens

If you’re not a documented citizen, you do not have to reveal your immigration status to any government official. If you are arrested, you have the right to call your consulate or family, or have the police inform the consulate of your arrest.

If you’re being held on suspicion, you have the same rights as regular citizens. If being held specifically for suspicion of violating immigration laws, your rights are a bit different. Either way, you shouldn’t talk until you connect with an immigration lawyer.

Do not talk to ICE without talking to an immigration lawyer first. Now your immigration (“A” number) if you have one. Visit the National Immigration Project of the NLG for additional guidance and information.

Special considerations for transgender and gender nonconforming people

Trans and gender nonconforming people are targest of police and other prisoners more so than other marginalized groups. This, especially, is where solidarity comes in to help protect for those with privilege. When you have an opportunity to show up in solidarity, you should do so.

If you’re arrested with someone who is a member of the LGBTQ community, you can ask the officer if someone of the LGBTQ liason unit is available to assist.

Special considerations for differently abled or people with medical conditions

ADA laws make it unlawful to be discriminated against, including by the police. However, that doesn’t always happen. When attending protests, it is best to be prepared and have prescriptions and medication supply that will last for a few days. It is also recommended to have documentation to avoid controlled substance suspicion or charges.

The only way to have access to medications in detainment and under arrest is with a doctor’s note. Be sure to let others in your affinity group know about this. It is also recommended that you let your medical doctor know that you’re planning to participate in civic engagement, so they can be aware to look out for a letter from police and/or jails confirming your patient status. If you would prefer the doctor not use your name in their confirmation, provide your doctor with a photo and have your doctor refer to you as “the patient.”

Minors

Anyone who is 18 years old or under without documentation may be processed as a juvenile. In cases such as these, officers may attempt to contact a parent or guardian to get information. Minors are not usually released to anyone except the custody of an adult.