How cops, corporations, local government, and the media fueled an undemocratic process to build a massive police training center one year after #DefundThePolice uprisings

Anyone listening to the virtual Atlanta City Council meeting on September 8, 2021 could hear the chants: “Stop Cop City!” It was a Wednesday night, and tensions were high. Protesters had gathered outside the houses of council members, outraged as discussion of a controversial proposal began. The police were on their way.

The matter before City Council was a proposal to raze 85 acres of Atlanta’s South River Forest and replace it with a new police training center. Reflecting the center’s plans to include a mock city for police and fire training, organizers who mobilized against the plan had dubbed the proposed facility “Cop City.” If the proposal passed, one of Atlanta’s critical remaining greenspaces would be destroyed and replaced with a massive, toxic, and noisy training center. The footprint of policing in Atlanta would expand significantly, just one year after nationwide uprisings demanded divestment from policing and investment in community-based safety.

The council meeting had begun the day before, but 17 hours of pre-recorded comments from over 1,100 Atlanta residents delayed the discussion, as council members spent most of Tuesday and Wednesday listening to the playback. A crowdsourced tally of the comments completed by local organizers (myself included) left little doubt about where those who called in stood on the proposal. Following months of tireless organizing and political education efforts from #StopCopCity organizers, approximately 70% of callers ardently opposed the proposal, offering reason after reason that their representatives should vote it down.

The minority who called to support Cop City were from one of three groups: a handful of firefighters, at least 30 police officers, and a large number of self-identified residents of the disproportionately white and wealthy Buckhead and Northeast Atlanta area. Pro-Cop City callers used the language of white flight, invoking the “uptick in crime” and threatening to leave the city if something wasn’t done.

On the other hand, those who opposed Cop City called from every other district, in addition to the area in unincorporated Dekalb County where the facility would be built. They represented all areas, classes, and races of Atlanta. By my count there was not one person who called in from any neighborhood near the proposed construction site who supported the project.

Even then, public comment was one relatively small slice of the opposition to Cop City. In fact, few issues have so clearly unified diverse interests across Atlanta. For months leading up to the vote, community organizers pursued a variety of tactics including circulating petitions, holding direct actions and banner drops, facilitating community education, canvassing regularly, building cross-issue coalitions, and holding town halls.

The campaign brought together police and prison abolitionist organizations, environmental justice and preservation organizations, civil and human rights nonprofits, and even neighborhood associations near the proposed site—including the East Atlanta Community Association, the Grant Park Neighborhood Association, South Atlantans for Neighborhood Development, and the Kirkwood Neighbors Organization, each of which passed resolutions opposing the proposal. Grassroots organizations that mobilized against the proposal included Defund APD, Refund Communities, the Atlanta Sunrise Movement, Community Movement Builders, the South River Forest Coalition, A World Without Police, and autonomous organizers working under the banner of “Defend the Forest.”

And yet, when playback of public comment ended and the council’s discussion began, council members largely failed to acknowledge the hours of public comment they had just heard—much less the far-ranging movement that produced such overwhelming dissent. Ultimately, the Council voted by a margin of 10-4 for the creation of the $90 million facility premised on the destruction of at least 85 acres of the South River Forest.

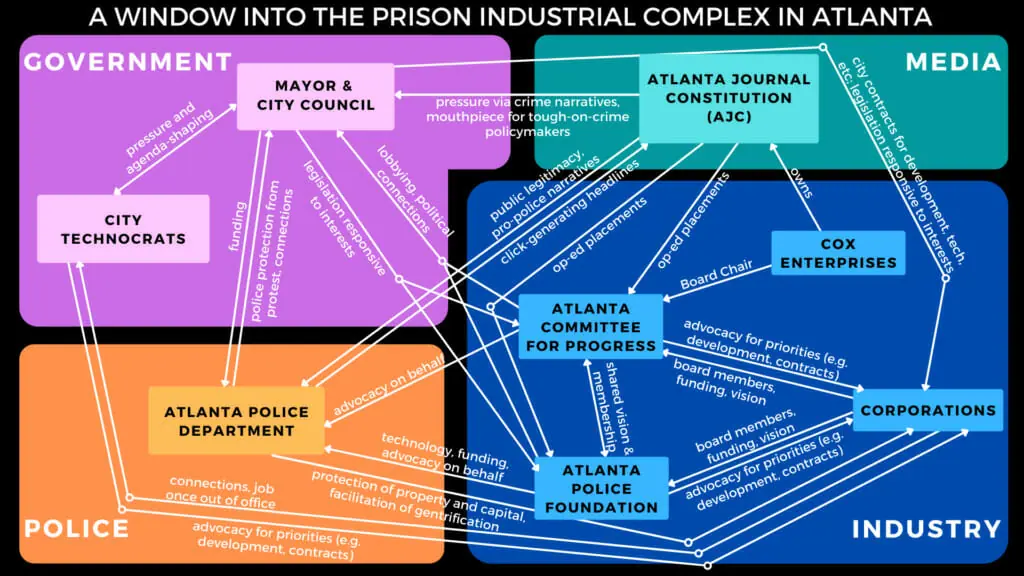

The City Council’s actions raise a question: how could there be such overwhelming public opposition to a proposal, and yet so little consideration from those in power of whether to push it through? Making sense of city leadership’s blatantly anti-democratic actions requires understanding how the prison industrial complex (PIC) functions in practice to expand policing and punishment at enormous human and environmental cost. Ultimately, the Cop City story in Atlanta offers a window into how the actors that make up the PIC—corporations, governments, media, police, and others—work in deadly harmony to suppress political dissent, subvert democratic engagement, and protect profits.

As geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore explains, the concept of an industrial complex dates back to President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1961 farewell address to the nation, in which he warned that the “wide-scale and intricate connection between the military and warfare industry would determine the course of economic development and political decision-making for the country, to the detriment of all other sectors and ideas.” In other words, as the country’s reliance on—and industry surrounding—war-making grew, it would re-shape the political and economic system around itself such that mass militarism would become a central feature of basic governance.

An industrial complex disguises infrastructures of mass misery—such as prisons, police, and militaries—as seemingly inevitable facts of life. Our system asks not whether endless war-making will be a staple of our political system, but rather to what extent. It asks not whether we will lock humans in cages, but rather how many people we’ll lock up and how we’ll do it.

The prison industrial complex (PIC) was initially theorized and popularized by those such as radical political theorists Mike Davis and Angela Davis, journalist Eric Schlosser, and the organization Critical Resistance—though as historian Dan Berger explains, like any vocabulary of resistance to policing and imprisonment, the PIC has deeper roots in the struggles of incarcerated radicals such as those in the North Carolina Prisoners Labor Union.

The PIC is the web of interests that create, sustain, expand, and depend upon the punishment system for their power, profit, or both. As a concept, the PIC is enlightening and overwhelming for the same reason: the sheer scope of that which it seeks to describe and explain. Whereas the more mainstream term “mass incarceration” describes the scale and often racial concentration of the U.S. prison system, the PIC is both further reaching in the systems it describes as well as explanatory in nature.

The PIC gives us language to understand how, over the past 50 years especially, our society has been shaped around the punishment system. This re-shaping has resulted in a set of interests that rely on the punishment system for their basic functioning and “success,” leading them to support the defense and expansion of that system as critical to their own survival.

What are these interests? The PIC includes politicians across the political spectrum who depend on anti-crime messaging to ensure their own (re-)election; corporations that pursue lucrative contracts to be found in the construction, technology, and service needs associated with policing, imprisonment, and surveillance; state and local governments that turn to prison and jail construction as perceived revenue sources; banks that specialize in prison and other carceral facility bonds; the media that generates clicks and revenue from fear mongering crime headlines; developers that rely on police to clear the way for and protect capital investments; and carceral actors such as police and prison officials who grow their power by growing society’s reliance on punishment.

People often interpret discussion of the PIC as a claim that the creation and expansion of the punishment system was one big conspiracy—the product, perhaps, of a couple corporations secretly pulling the strings of government to line their pockets. And certainly, many actors in the PIC act conspiratorially, making backroom deals, purchasing influence, and promoting disingenuous fear mongering talking points.

But the power of the PIC, like any industrial complex, is that it doesn’t need conspiracy to function. Instead, the PIC describes the way in which our political and economic system has been shaped around the punishment system, such that a departure from mass punishment would destabilize the foundations of the status quo. Indeed, as Gilmore writes, “The main point here is not that a few corporations call the shots—they don’t—rather an entire realm of social policy and social investment is hostage to the development and perfection of means of mass punishment.”

In other words, those who benefit under the existing racial capitalist system have a material stake in perpetuating policing and imprisonment, and rationalizing those efforts through rhetoric of public safety and fighting crime. As scholars David Correia and Tyler Wall explain, “The nature of police is to establish the necessary conditions and relations for the accumulation of capital.” Capitalism’s success depends on the disciplining of those who are bound to serve it, and the criminalization of those who would threaten it.

As Schlosser writes, beyond a set of interests, the PIC is “a state of mind,” one formed around a capitalist economy hardwired to the punishment system. The idea is that many of our core governing institutions, whose existence and power ensures our current status quo of mass inequality, are dependent on the punishment system for their own survival. In other words, there can be no capitalism without policing and prisons.

It can be difficult to understand the PIC in practice. What does it mean for the actors that constitute the PIC to be reliant on the punishment system? How do we chart the connections between them?

The PIC is a national and global force, but one that manifests locally, meaning how it works looks different across time and place. Just as importantly, the PIC is a web, not a flowchart, meaning that each actor within it interacts with one another. There is not one clear point to jump in. We’re mapping relationships of power—not describing a cause-and-effect sequence of events—in a web that includes corporations, developers, nonprofits, the police, government officials both elected and appointed, and the media, among others.

Even still, we can take an editorial released from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as a launch point to begin mapping some of the relationships that keep policing, prisons, and punishment alive and well in “The City Too Busy to Hate.”

The full City Council first considered the Cop City ordinance, which was introduced two months earlier, at a meeting in mid-August 2021. However, previous months of organizing culminated in a narrow vote to delay the proposal, dealing a significant blow to the plan’s proponents and opening space to continue organizing against the proposal.

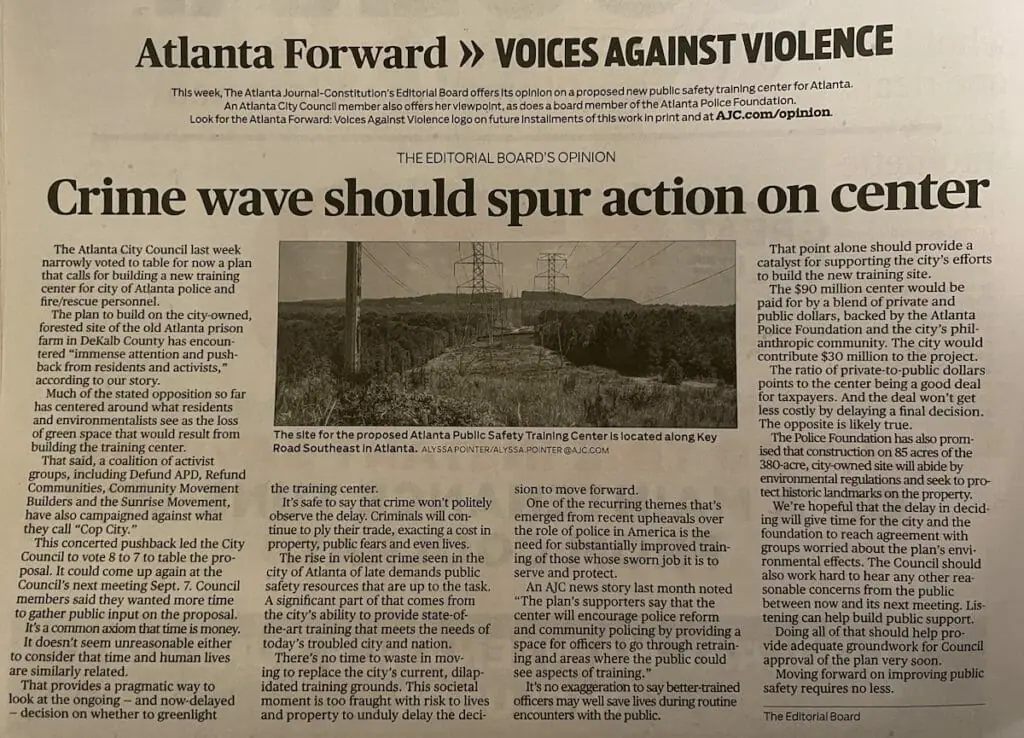

The week after the City Council voted to table the Cop City ordinance in August, the Editorial Board of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC) published an editorial urging the creation of Cop City and denouncing the delay of the legislation that would authorize it. The “crime wave,” the editorial argued, left no time to waste in creating Cop City.

“Crime won’t politely observe the delay,” the editorial board wrote, stoking fear that “criminals will continue to ply their trade, exacting a cost in property, public fears and even lives.” In the board’s version of events, any deaths or injuries associated with the so-called crime wave were actually the fault of the activists and organizers seeking to stop the passage of the proposal.

The Board makes no mention of the fact that its very premise—that the new facility is urgently needed to combat Atlanta’s supposed spike in crime—is a disingenuous one. In fact, the facility, even once approved, would not be built for multiple years, regardless of the support behind it. Even if we assume the board’s genuine concern was an urgent, immediately pressing “crime wave,” the new police and fire training facility would have no bearing on it in any case. Indeed, as one of the chief proponents of the proposal himself noted, the facility would not be ready for at least two years.

The same day the AJC ran its editorial in support of Cop City, it also published an opinion piece by Robert C. “Robin” Loudermilk, Jr., the president and CEO of the Loudermilk Cos (also the Board Chair for the Atlanta Police Foundation—more on them later), questioning the priorities of the city council members who voted to table the ordinance, and urging its passage.

Likewise, earlier in the month, the AJC had published an opinion piece by George Turner, a former Atlanta police chief, who calls Cop City “the most important and impactful public safety initiative City Council has considered in more than three decades.” Several months prior, the AJC had published an opinion from President and CEO of the Atlanta Police Foundation Dave Wilkinson extolling the virtues of a facility he deemed to be “the most important commitment that our city has made to enhance public safety in 50 years.” Wilkinson had been given space in the paper of record back in January, as well, to warn the public that violent crime was out of control and could only be solved through further investment in policing.

Atlanta’s dominant newsource and legacy newspaper’s full-throated endorsement of Cop City was solidified by its failure to publish any opinion pieces opposing the new facility.

Why was the AJC’s coverage and opinion space so one-sided? What is the paper’s stake in policing? There are some obvious answers reflecting the adage that “if it bleeds, it leads”, meaning that in an increasingly corporatized media landscape, crime headlines generate increased clicks and, crucially, increased ad revenue. But there’s also a deeper and related answer, that we can explore by looking at an omission in the editorial board’s August piece urging the creation of Cop City and condemning those who delayed it.

While the AJC made clear where it stood on the Cop City proposal in its editorial and surrounding coverage, the paper left unsaid a key relationship that might influence its coverage: the AJC is owned by Cox Enterprises, whose CEO Alex Taylor is chairing the fundraising campaign to raise over $60 million in private and “philanthropic” funding for Cop City.

This disclosure didn’t make it into the piece until online pushback pointed out the conflict of interest. And it wasn’t the first or last time the AJC failed to disclose that the project it was ardently supporting was being spearheaded by its owner.

In addition to serving as CEO of Cox Enterprises, Alex Taylor chairs the Atlanta Committee for Progress (ACP), which describes itself as “a partnership between the city’s top business, civic and academic leaders, and the Mayor of Atlanta to support positive change in our city.” Founded in 2003, ACP focuses particularly on development projects in Atlanta, and its board is mostly leaders of major corporations, including Delta Airlines, Equifax, Chik-fil-A, Koch Industries, AT&T, Home Depot, Mercedes Benz, Coca-Cola, and Georgia Power, as well as a number of Georgia-based university presidents and foundation representatives.

In April 2021, ACP released a statement in support of the facility, and noted that then-Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms had “asked Taylor to lead a capital campaign to seed the initial private funding for the project.” Taylor agreed.

Setting aside the clear conflict of interest inherent to the paper of record reporting on and failing to disclose a key project of its owner, why might Taylor, the ACP, and the corporations ACP represents be so interested in Cop City? Understanding ACP’s commitment to policing requires understanding the relationship between policing and the “development” it advocates.

The ACP’s stated mission is to “accelerate Atlanta’s competitiveness for attracting residents, businesses and investment, with a high priority on public safety, while expanding economic opportunity for all.” And in Atlanta, as elsewhere, development and “investment” have translated to gentrification.

As southwest Atlanta-based organization Community Movement Builders explains, gentrification is an economic process in which outside developers and others purchase homes and real estate in communities, driving up the cost of living and pushing out poorer and often Black residents from their homes. Gentrification draws higher-income white people who are more likely to call the police, and is most often packaged as “development” that will bring various amenities to gentrifying neighborhoods—not for those who live there, but rather for those who will move there.

ACP’s fingerprints are all over gentrification in Atlanta, which faces an ever-worsening affordable housing crisis that is disproportionately pushing low-income Black residents further out of the city. For example, under previous Mayor Kasim Reed, ACP created The Westside Future Fund, which uses language of “renewal” and “redevelopment” to push development projects on Atlanta’s westside, a predominantly poor and Black area of Atlanta. The Westside Future Fund accelerates exactly the kind of “development” that those such as Community Movement Builders are resisting.

Or consider ACP’s key role in the creation of the Beltline, a “multibillion dollar development project” that has rapidly gentrified its surrounding areas. From 2011-2015, for instance, the half-mile surrounding the Beltline saw as much as a 26% higher increase in housing prices than other areas. The Beltline continues to push longtime residents out, and as its construction extends into Southeast and Southwest Atlanta, the problem worsens. The greed of developers has overtaken any good (if naive) intentions of those who conceptualized the Beltline, leading many to resign from the partnership overseeing it.

We might also look at the $5 billion development plan for “the Gulch,” an area of Downtown Atlanta given over for development to the California-based CIM Group. The project immediately raised concerns from organizers who noted that the deal would privatize a significant amount of public land, while funneling nearly two billion dollars worth of taxpayer money back into CIM rather than communities.

The Gulch deal started under Mayor Reed’s administration, and the Bottoms administration sold it to the public by advertising the supposed $45 million worth of “benefits” that CIM would provide to the city. But as organizers gathering in a coalition called Redlight the Gulch argued, any final “benefit” paled in comparison to the $1.9 billion (originally $2.5 billion) worth of public money channeled into the project by designating the area a “tax allocation district.” Through a tax allocation district, most of the tax revenue generated through the project would be cycled back into paying for the private development rather than going to schools and other public services.

In other words, through the Gulch deal, taxpayer money would be used to fund the privatization of public space, the acceleration of gentrification, and the expansion of policing that would push people out. As the American Friends Service Committee put it, “the cruel irony is that communities that are being displaced are being forced to pay for their own gentrification through projects like the Gulch.”

What does the ACP have to do with the Gulch deal? Everything. The deal was first confirmed at a meeting of the ACP, and continued to be fleshed out at subsequent ACP meetings held in the offices of Cox Enterprises that involved Mayor Reed as well as CEOs of organizations including Home Depot, Suntrust, UPS, Georgia Power, Chik-fil-A, Mercedes-Benz, and others. The ACP continued to have the mayor’s ear throughout the Bottoms’ administration.Each of these projects reap massive private profits underwritten by public funding for the developers and other corporations represented by ACP. But for communities, they reap displacement. They are dependent on displacement. And displacement is not passive, but rather an active process facilitated in part by the police.

Gentrification requires policing. Police protect property and capital investments, and clear out the homeless and poor who threaten rosy conceptions of development and prosperity that accompany new projects. Police facilitate gentrification through increased police presence, ticketing, and arrests for “quality of life” offenses that drive out and disappear people into the criminal legal system, and by ensuring investors that their investments will be “protected” from the poor who would ostensibly threaten it. And the local laws that police arrest under are passed, expanded, and justified by those on city council, as well the corporate interests who lobby them.

A core function of policing, as many have argued, is to protect capital and property—to act as “capital’s security forces.” Look no further than the summer of 2020, in which police were mobilized rapidly to quash uprisings against ongoing police violence that “threatened” property. As organizer Cheryl Rivera writes, “There is no resistance to capitalism that has not been met with batons.”

Police patrol the border between the “haves” and the “have nots”, the rich and poor, the new white residents and displaced Black residents. And they are not just border patrol, but also border expansion, doing the work of clearing out those deemed threatening to investors and developers.

In Atlanta, police are given this duty rather explicitly. As one former Atlanta Police Department officer described to Mother Jones in September 2020, his orders were to begin more heavily policing the gentrifying area surrounding the Bedford Pines Apartments—to give tickets and make arrests so that Section 8 residents who avoided eviction via rent hikes could be evicted through a criminal record instead. As the former officer explains, his orders were to “lock up as many people as possible so we can make these apartments vacant and we can knock ’em down.”

If police protect capital and clear room for its expansion, it should be no surprise that those who control capital return the favor. ACP and the interests it represents know that police are necessary for all that goes into wealth accumulation, making their collaboration with the police a matter of course—a natural partnership between those who protect capital with guns and handcuffs, and those who protect the protectors of capital with funding, facilities, and technology.

Think back to ACP’s mission, which explicitly links “public safety”—policing—with attracting “businesses and investment.” There are no secrets here, no conspiracy—just the interlocking forces of policing, gentrification, and wealth accumulation. It should be, then, no surprise that ACP’s Board Chair agreed to spearhead the fundraising for Cop City, or that the media outlet he owns reported so favorably on the initiative.

The Atlanta Committee for Progress is not corporations’ only front for expanding policing and consolidating power and wealth in Atlanta. In recent years, as a report from the organizations Color of Change (COC) and Little Sis explains, police foundations have become a key site for corporate sponsorship of policing.

Police foundations are private, nonprofit organizations that operate in most major U.S. cities to raise funds for local police departments, expand police budgets, donate technology, supplement surveillance systems, test new weapons and equipment, and serve as Public Relations for the police. Corporations from every major sector pour into police foundations, through which money and technology is then channeled into policing while remaining shielded from most transparency and accountability mechanisms. Police foundation funding is often used in particular to fund projects that the public might otherwise reject, such as particularly invasive or expensive surveillance technology.

For corporate donors to police foundations, “donations” might be better understood as investments. As the COC report documents, many corporations are “donating with one hand, [and] profiting with the other.” Beyond the general return on investment to be found in greater police protection for capital and surveillance of those who would threaten it, some corporate “donors” of police foundations (who often also sit on police foundations boards) quickly become contractors for the police they fund—especially when it comes to technology and surveillance companies, who gain lucrative contracts with police departments.

It’s worth recalling, here, Gilmore’s observation that philanthropy represents twice-stolen wealth—stolen first through exploitation of workers and second through its shielding from taxes—and that foundations are where this wealth is held. In the case of philanthropic funding channeled through police foundations, twice-stolen wealth is channeled into creating the conditions for greater wealth concentration and further exploitation by the corporations providing the funding. Through police foundations, as the COC report puts it, “Corporate money flows into corporate priorities, such as heavily policed and surveilled retail areas and gentrified neighborhoods, while vital community needs are underfunded.”

In Atlanta, that work happens through the Atlanta Police Foundation.

Understanding the PIC is about understanding relationships of power, and the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF) is a key power broker in Atlanta. Making a tidy $300 thousand salary as of 2019, APF’s President and CEO Dave Wilkinson is a core player in Atlanta politics, drawing on a broad array of political and corporate connections stemming from both his work at APF and his 22 years serving U.S. presidents in the Secret Service. Most recently, Wilkinson was named to newly-minted Mayor Andre Dickens’ transition team.

With significant funding, corporate backing, deep relationships, and a direct line to the police, APF’s leaders have direct access to the mayor’s office and city council members, and expend significant resources lobbying them for police expansion.

APF has been a scourge to Atlanta’s Black, homeless, and otherwise vulnerabilized communities for nearly two decades. Founded in 2003, APF funds “Operation Shield,” a network of over 11,000 surveillance video cameras and license plate readers that has earned Atlanta the status as one of the most-surveilled cities in the world. Local business owners in Atlanta are encouraged to integrate their cameras into the security system, which is headquartered at the Loudermilk (sound familiar?) Video Integration Center. APF operates a number of other programs as well, including Operation Aware, a “predictive policing platform and criminal analytics software partnership with Microsoft.” In 2021, APF launched the Buckhead Security Plan, an expansion of Operation Shield that was funded by a variety of Buckhead-based associations, APF, and even three city council members who devoted part of their budgets to expanding surveillance in the overwhelmingly white and wealthy Buckhead area.

APF’s latest project? Designing, funding, and lobbying for the “Public Safety Training Center,” or Cop City. APF has been the key force behind the Cop City ordinance, selecting and drawing up plans for the site, evangelizing the need for the facility publicly, and committing two-thirds of the proposed facility’s price tag—$60 million—to be paired with $30 million in public funds.

And while APF’s “public engagement” around the proposal only began in summer of 2021, the plan was in the works since as early as 2017. Indeed, a 2017 presentation by APF recommended 160 acres of the Atlanta forest for the creation of a new police training facility, estimating a price tag of about $80 million. It was around the same time that APF began to approach city council members about the facility. And yet, for some reason, “public engagement” on the proposal didn’t begin until summer of 2021—and only then, because organizers took notice and began to agitate around the proposal—at which point it was fast-tracked with little public input.

But let’s back up, and take a longer look at APF’s involvement in making Cop City a reality.

In January 2021, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms signed an administrative order creating the “Public Safety Training Academy Advisory Council,” charged with offering recommendations on the development of the center. While the order required inclusion of community members on the committee, local journalists pointed out that ultimately zero community members were included. Instead, we saw the usual suspects: city officials, APF employees, and representatives for the Atlanta police and fire departments.

The advisory council met four times from January through March 2021, culminating in a set of recommendations that essentially rubber-stamped what APF had already proposed back in 2017: build Cop City on the Atlanta forest. In early June 2021, Councilmember Joyce Sheperd introduced APF’s legislation to do exactly that.

The legislation first went to the Finance Committee of City Council, where it would be considered on June 16, 2021. A couple days before the Finance Committee’s June 16 meeting, Wilkinson forwarded an email to the city’s Chief Operating Officer, Jon Keen. Keen began working for the city in 2018, leaving his job at Deloitte Consulting LLP to do so.

Wilkinson writes, “Jon, see below the message I received today from a prominent CEO. I wanted you to see this as an example of what I deal with each day.” Wilkinson withholds the name of the CEO, but notes that he serves on the Atlanta Committee for Progress and is “extremely frustrated by the crime surge and the lack of support for public safety over the last year.” Wilkinson lets Keen know that while “u [sic] will not hear this directly, they don’t believe the Mayor has shown real leadership.”

For context, at the height of the uprisings sparked by another round of police murders, then-Mayor Bottoms authorized $500 bonuses paid for by APF for every police officer, followed by a March 2021 announcement that she would be adding 250 officers to the police force. And in 2021, the Mayor proposed and City Council approved a $15 million increase to the police budget, the largest increase for any city department. To Wilkinson, apparently, this was all evidence of a lack of support.

Wilkinson continues: “I believe the Mayor has the opportunity to show real leadership on this critical issue by calling each member of the finance committee and let [sic] them know with no uncertainty that we will build the training center at the key RD [sic] site and we plan to move forward with speed due to the urgency of the matter for our city and the negative message/lack of support if we hesitate. She could encourage them to approve the lease and assure them that community engagement sessions will be held.”

Wilkinson also references a call with Keen: “You mentioned in our call council members are looking for a cover and that is absolutely correct. However, the fact they would hesitate moving forward on such a critical issue shows they can’t seem to get out of their own way. To give in on this critical matter for Atlanta due to a small group of environmentalists in Dekalb just shows how weak they really are and I am afraid the Mayor will look weak once again by the [council members’] hesitation” (emphasis added).

There’s a lot to unpack here, and we haven’t even gotten to the forwarded email from the anonymous CEO and ACP member. In short, Wilkinson is saying: CEOs are angry, it’s the mayor’s fault, and she can reverse course by bullying city council members into passing this ordinance with a promise of future community engagement sessions.

Wilkinson knows that council members are “looking for a cover”—a cover, presumably, to vote for a proposal that so clearly contradicts public will and had proceeded up to that point without even pretense of community engagement. Then comes the email from the unnamed CEO and ACP member:

Sorry to send you this note on a Sunday, but I am really struggling with the continued challenges facing Buckhead. The shootings over the past few weeks, parties in the streets this weekend and the water boys running around on scooters at Lenox and 400. I am having a really difficult time continuing to support the police department and why Buckhead should not leave the City of Atlanta.

We need to start having an honest conversation about what is really going on. If the mayor is holding the police back[,] let’s talk about it. If the courts are not doing their job[,] let’s talk about it. If the laws need to be changed to make some of this crazy stuff illegal[,] let’s talk about it. But the current situation must stop ASAP or I and others will have to turn all of our support toward the Buckhead City movement. (emphasis added)

Buckhead is the disproportionately white and wealthy epicenter of conservatism in Atlanta, and is currently the site of the “Buckhead Cityhood” effort to secede from the rest of Atlanta. Plainly, this email is a threat: “If you don’t get this situation under control, we’re going to white flight our way out of Atlanta. Build Cop City, arrest and incarcerate more people, or kiss your tax base goodbye.”

This email is a helpful elucidation of the PIC in Atlanta: capitalists (in this case, the Buckhead CEO) calls on their paid representatives (APF) to lobby the City (the mayor’s office and City Council) to expand policing and incarceration in Atlanta, to protect the interests of capitalists. And the entire process is backed by the threatened flight of white tax dollars.

As the Cop City proposal faced growing pushback from organizers and communities in July 2021, APF hosted a series of two “public input” sessions—sessions in which, presumably, the public would get to offer input on the proposal. This was not the case. As Mainline’s founding editor Aja Arnold reported for The Intercept, both Zoom sessions featured slideshow presentations from police representatives without providing any time for residents to speak. The chat function was disabled. APF co-hosted a third session in early September with council member Natalyn Archibong—who ultimately voted against the proposal—in which community members were once again not permitted to speak.

It’s hard to conclude that the sessions were anything other than staged to claim public engagement without genuine public participation. Generously, we could call it checking the box; realistically, we should call it manufacturing consent. Whereas one might expect a “listening” session to allow decision makers to listen to the public, the arrow ran in the opposite direction: what they meant was that the public would listen to decision makers, who would then justify their pre-planned decisions under the guise of having hosted listening sessions.

This isn’t conjecture. In early August 2021, after the first two listening sessions, APF Chief Operations Officer Marshall Freeman sent a set of documents to Keen and the city’s Deputy Chief Operations Officer Jestin Johnson for review, asking for feedback on a draft report detailing APF’s community engagement efforts. The draft report described the “listening sessions\’\’ conducted by APF as having found “significant support for the project.”

This was a bridge too far, even for Johnson, who was actively supportive of the project. Johnson responded in an email:

Given the structure of the community listening sessions and questions received, you may want to consider striking the highlighted section “Our listening sessions and one-on-one conversations, however, found significant support for the project, particularly from residents who were fully briefed.”

Johnson continued: “I’m not sure if there would be agreed upon census [sic]. Unless there were other listening sessions outside of the two I attended, the feedback and questions would not necessary [sic] confirm overwhelming support.”

APF’s “community engagement” was a sham by any standards. But we don’t have to rely on an abstract sense of how much engagement is enough. As urban designer and Atlanta Beltline originator Ryan Gravel explained, if the proposed property were within city limits rather than in part of unincorporated DeKalb County, the process would have been a far more robust one that included meetings with and recommendations from the surrounding neighborhoods, the committees of the Neighborhood Planning Unit (including at least Land Use and Zoning, Public Safety, and Parks committees), and eventually the full Neighborhood Planning Unit for the area. Only then would the proposal have begun to work its way through committees of the City Council.

Organizers who saw these sessions for what they were proceeded to host their own community engagement session on August 5 called “The People’s Town Hall,” providing community members with a true opportunity to speak on the proposal. Nonetheless, the ordinance ultimately made its way out of the Finance and Public Safety Committees, coming before the Full Council on August 16. At that point, the campaign to stop Cop City was in full swing, successfully leading to the tabling (delay) of the ordinance by a razor-thin margin of 8-7.

The sticking point for the city council members who voted to table the ordinance was ultimately the lack of engagement, particularly with residents of the area surrounding the proposed site. As one council member noted before making a motion to table the ordinance, APF had not even reached out to the county commissioner who represented the area of unincorporated DeKalb County where the facility would be built.

One of APF’s selling points for the proposal was a provision in the ordinance was that APF would “regularly convene a Community Stakeholder Advisory Committee…to make recommendations around community engagement, key siting, design, and operating details.”

What would be the actual role of the Community Advisory Committee? APF and the mayor’s office had some thoughts.

In late August, after the ordinance had been temporarily delayed, Keen forwarded an email to Wilkinson, Freeman, and Johnson from a DeKalb County resident who would later become a member of the Community Advisory Committee. The member sought to understand the role of the Advisory Committee and what input would exist through the committee for residents of the area surrounding the proposed site:

For instance, if the Community Advisory Board opposes certain changes during the planning process after the ground lease is approved, what would incentivize the city/APF to make changes in response to the community\’s need versus proceeding with their plans which would be legally protected after the agreement has been approved?

A separate conversation ensued between APF and city representatives on the email thread. Keen offered two options for the role of the community board going forward: the first option would give the Community Advisory Board a vote on key items that would “influence subsequent steps in the process.” The second, far more robust option would require a Community Benefits Agreement negotiated by the Advisory Board, which would be “a binding document that would influence subsequent steps in the process.” Keen suggested the group choose option one. Johnson responded agreeing that option one would be preferable, while offering caveats to even that level of influence for the advisory board.

Freeman thought otherwise: “Dave [Wilkinson] and I talked a bit this morning about this. Some of our immediate thoughts are to ask each of these communities to approve the plan as it currently stands. We would then push for alignment on language that states any significant changes made to the plan shall be reviewed and/or approved by the Advisory Committee.”

Keen then responded with the kicker:

I don’t believe we can start insinuating that the plan is final already. We have been stating that the plans will be finalized over the coming months in consultation with the community. I don’t think it will be an easy lift for this group to approve the plan ‘as-is’. They will be reluctant to support any plans until they feel like their thoughts have been clearly incorporated. (emphasis added)

Keen also cautioned against a Community Benefits Agreement, as “neighborhood leaders will get pressured to include as much as possible in that agreement since it will be seen as the only opportunity for commitments.”

Was the plan final or not? In the minds of APF’s leadership, it certainly seems that way. But as Keen cautioned, communicating as much to the advisory committee would be a bad move.

After the Cop City ordinance was passed in September, the advisory committee was formed, holding its first meeting in October 2021 in a process that has already come under fire for its lack of transparency. Committee members are still confused about exactly what powers the committee has. As one committee member said, “I’m not seeing where the process is really going to have any accountability from us in the way that was promised back when that [committee] was approved… This committee definitely needs some kind of final benefits agreement that we all sign onto.” As APF made clear back in August, that’s not something they are interested in. Indeed, most recently, the committee chair announced a ban on committee members speaking to the media.

As Advisory Committee members work from the inside to delay or reduce the harm of the proposal, organizers continue to agitate around the proposal from the outside. Protests continue, as does police repression of those protests.

Speaking of the police: where were they in all of this? Put simply, doing what police do: acting as the footsoldiers of capitalism and the PIC by quashing rebellion against the destructive status quo of environmental and human exploitation.

On the night of the Cop City vote, protesters showed up to council members’ houses where they were virtually participating in the council meeting. Protesters chanted “Stop Cop City,” urging their representatives to abide by the public’s wishes as made clear by the previous 17 hours of public comment. Police appeared promptly, arresting 11 individuals and taking them to the city jail.

It’s worth stating in plain terms the sequence of events: police showed up to arrest individuals who were protesting the decision of city councilors, who were pressured by the representatives of corporate interests to pass legislation that would expand policing in Atlanta, all in the service of further development and corporate profits. In this sense, police repression of protesters represents a rather clear case of the PIC defending and perpetuating itself. No conspiracy, no laws broken—just a set of mutually-sustaining and co-dependent interests acting as expected to keep doing what they do: amassing profits and power.

Policing is not and has never been a neutral institution. Police know their power, and they work with their supporters to wield power effectively to get what they want. This is certainly the case in Atlanta. Why else would city council members feel that they need “cover” to vote for a proposal? They knew that the public opposed it, but that policing’s representatives supported it. And at the end of the day, they would side with police and their corporate sponsors.

Even those who ultimately voted against the Cop City ordinance clarified that they supported the facility, just not at the proposed location. Openly challenging the police seems to be unthinkable for Atlanta’s lawmakers, and not without reason. As one journalist shared on the night of the vote in favor of Cop City, “An Atlanta City Council member I just spoke to said the #CopCity vote is especially tough because, if they vote NO, APD and AFRD might not be as helpful in their community.”

The ongoing story of Cop City in Atlanta is a window into how the PIC works to protect policing and profits at major human and environmental cost.

The relationship between the actors that constitute the PIC is symbiotic. They work together, not in a grand conspiracy, but rather through mutually-reinforcing relationships under a racial capitalist system that produces mass racialized poverty and hyper-concentrated wealth—a system that needs police to manage the former and protect the latter. In a system organized around profit, capital’s representatives and governments work together to pave the way for both future capital accumulation and the punishment infrastructure needed to secure it. Corporate-owned media rationalize and justify policing through sensationalist reporting that drives their own revenues. And the police crush dissent against the system that results in so much premature death and suffering.

Meanwhile, the relationship between the PIC’s actors and the rest of the public is parasitic. If constructed, Cop City will weigh most heavily on the predominantly Black communities closest to the proposed site, who will be forced to live under additional noise and land pollution. Fortified police presence will continue to result in police murders, arrests, and jailing, disproporationely of Black and poor communities. And climate disaster will hasten as Atlanta’s canopy is destroyed, natural flood-prevention mechanisms are dismantled, and temperatures rise.

If Cop City illuminates the devastating implications of how the PIC works in practice, it also teaches us how ongoing multiracial movements against the PIC can build power for a different world. Indeed, the broad-based movement to stop Cop City picked up significant wins, including amendments to the final legislation that reduced the acreage for the facility from 150 to 85 acres. Perhaps most importantly, organizers mobilized a broad group of people who found themselves newly radicalized as they watched city leadership ignore the rapidly growing and overwhelming consensus against Cop City.

The story is not over. Today, the people continue to struggle in organized and autonomous movements working to halt the destruction of the forest. And even if the story ends in defeat and Cop City is built, #StopCopCity organizers have shown exactly why we fight: because, as organizer Kelly Hayes reminds us, to give up is to ensure defeat, whereas to act is to leave ourselves a fighting chance for a better world.

A world without the PIC is possible. It’s up to us to build it.

Pingback: Cop City’s ‘Ivory Tower’: Georgia State University is Ground Zero for Militarized Policing