“Half of me like was like, ‘Have I lost my fucking mind?’”

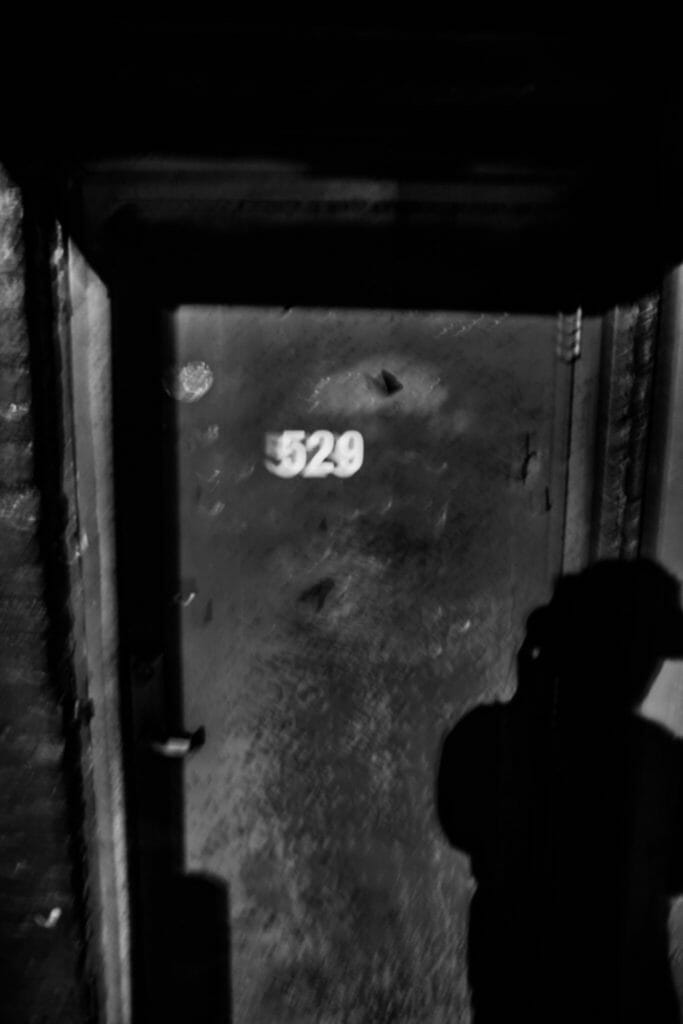

The year was 2016 and Atlanta-based political artist Joseph Guay was flushing $25,000 down the toilet. He was in the throes of constructing a life-sized panel of the proposed $20 billion wall for the U.S.-Mexico 1,989-mile border. With the help of 12 undocumented immigrant construction workers, Guay built a 40-foot wall composed of steel and concrete to help people wrap their heads around what such a wall would actually look like.

“The Border Wall” public art installation resided on the corner of 10th Street and Howell Mill in West Midtown of Atlanta for a year as an offering to anyone to use to express themselves. The value of this exhibit didn’t lie in potential dollar signs; instead, it was the message behind it and the experience it curated for others.

“No one was gonna put up a 40-foot, 40,000 pound wall in their house,” Guay told me during our interview at Murphy Rail Studios in Southwest Atlanta, a newly renovated studio that houses and showcases Guay and other artists’ work. While the story of “The Border Wall” fascinated me, I found myself distracted. I sat in a folding chair across from Guay, gazing at a clock on the opposite wall that was stuck at 2:22, facing two rows of seven empty desks that had been scribed by children and teenagers in chalk.

Never again. I’m a single issue voter. We’ll vote you out. Am I next? Books, not bullets. Help us. Graduation, not funerals. When will we be enough for you?

We were sitting in front of Guay’s powerful “Missed Attendance” exhibit. My mind wandered to the students the 14 empty desks represented, and I wondered how many people total were killed in school shootings last year. The small pieces of paper decorated by facts and statistics mounted along the smaller sculptures nearby—a clear backpack filled with bullets, pencils made with bullet casings, a stack of paper with the words “Am I next?” written in childlike handwriting on the top—would probably tell me.

But I was sitting in the chair, the Violent Femmes was playing, and Guay was explaining “The Border Wall.” He explained that he didn’t always do political art; the shift came in 2016, with the news at the time being riddled with Trump’s conversations of building a border wall, full of vilifying narratives of immigrants and their families.

“Trump wants to build a border wall, all these people say they want a border wall, so I’m gonna give them a wall,” he explained, taking us back to what he was thinking when he decided to launch the project. “And I’m gonna have them stand in front of it and see how they feel.”

The point of these previous successes was to put Guay in a position to flush that 25 grand down the toilet with the construction of “The Border Wall.”

By that time in his career, Guay had completely moved away from decorative, clientele-based art, and the wall was a big step out of that zone. It wasn’t the first time he stirred the controversy pot with his art, though. Prior to “The Border Wall,” Guay’s exhibit “Duel // Dual” explored the duality of humanity and how there are two sides to every coin. Take guns, for example. One use is protection, the other is crime. The ego: self-loathing and self-confidence. “Remnants of the Human Condition” focused on the tragedy of Trayvon Martin’s death, with pieces consisting of black hoodies and other smaller sculptures, like that of a bag of Skittles. To Guay’s surprise, these pieces were well-received in the art community—and people did actually buy them, including Sir Elton John. However, that’s not the point.

The point of these previous successes was to put Guay in a position to flush that 25 grand down the toilet with the construction of “The Border Wall.” The media caught wind of the story (of course it did) before its unveiling and the exhibit garnered media attention from the likes of CNN, ArtsATL, and Latin media outlets such as CNN Español, Notimérica, and Telesur.

“I think they were shocked that an American would do that,” says Guay. “In a lot of these countries, if you do something like that, you’re gonna get the hammer.”

Instead, Guay brings the hammer down through his work, never taking no for an answer, staying clear in his vision. Of course, this wasn’t always the case. Although Guay’s artistic visions and talents were recognized and fostered in his youth—he received a full-paid scholarship to Savannah College of Art & Design as a high school freshman—he combusted in frustration during his junior year when his family lost everything, making the move to Savannah and attending SCAD no longer a viable option. That year, he took all his pieces of art, threw them in a dumpster, and burned them all, with the hopes of never thinking about touching art again.

As I was listening to Guay’s story, it became clear there are two functioning aspects of him as an artist, and as a person. One operates in self-doubt while the other is completely self-assured. Relentless, even. The moments of self-doubt, fleeting yet glaring enough for him to ponder on, are punctuated by what sounds like Guay questioning himself as if from a bird’s eye view, looking down at his human form, raising the question: Have you lost your fucking mind?

“But it went back to this thing, like, I’ve never done anything like that,” explains Guay, always returning to moments of redemption sparked by artistic calvary, experiences defined by usually intense mental suffering. “I’d never done something that was that risky or challenging to myself or could potentially mess up a lot of clients for myself. There were a lot of things at risk.”

“The Border Wall” stirred some controversy and provoked confusion as well, as many in the art world couldn’t fathom why someone would spend so much of their own money for a public art installment—but once it was in the world, it created myriad experiences for all different types of people. The wall actually became a bridge, a space where someone could write “Fuck Trump” and another could walk up and write “Trump 2020,” and then talk about it. Guay witnessed people’s interactions with the wall first-hand, usually hanging at the site without letting anyone know he was the wall’s creator.

“There were a lot of times I’d be out there and I’d see people have real conversations on a human level,” remembers Guay. “I’d watch people bring their kids, and parents crying, telling their kids, ‘Look, this is where our country’s going. You should learn now that you don’t block people, you don’t make people outcasts, and you don’t segregate against others.’ Several times I’d watch police officers write on it and cry. There were military people that would tell me, ‘You know, I worked border patrol and I’ve seen some stuff, and it’s not right what we do.’”

Although Guay holds his own opinions about the issues his art centers on, the intention behind the work is to stay neutral. For him, what’s bigger than the fight between the opposing narratives surrounding these issues is the fight against misinformation. “Deep down, of course I hate everything that a wall stands for,” explains Guay. “[Through this work], I was getting real accounts of how it’s affecting people and not some news channel’s spin on it. You know, that doctoring of a story.”

While misinformation about the border wall President Trump pushes for lends itself to the ultimate delusion that any wall is going to keep everyone safe, Guay’s exhibit shows how futile a wall actually is. “It’s not like we suddenly build a wall and we’re in Utopia and no crime will exist,” he says. “Even the walls we have, people climb it in like 45 seconds. [The wall] is really for close-minded people who need to feel like that’s doing something. The guy who fences in his backyard and thinks his house will never be broken in.”

“The Border Wall” is currently stored at the Bakery in Atlanta, still open to the public to use for artistic expression until its next location reveals itself. It costs more money to transport the life-sized border wall than it did to actually build it, but this doesn’t mean that the wall’s work is over. With the current administration’s immigration policies and weaponization of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agencies, the wall could very well make another appearance.

But we were past that now, and our conversation merged somewhere else. I found myself back to that question of last year’s number of school shooting victims: thirty-five.

Once Guay has an idea, there’s no stopping him.

Thirty-five people lost their lives in school shootings in 2018. There were 94 school gun violence incidents that year, making it the deadliest and “worst year of school shootings,” according to the BBC. The Parkland shooting was the tenth of the year. On February 14.

The exhibit’s primary installment is 14 antique, metal school desks painted in blackboard paint with handwritten chalk notes on them. Guay acquired the desks after the Parkland shooting and had them ready for Atlanta’s March for Our Lives protest organized by Grady student and activist Royce Mann that spring. Originally hoping to take the exhibit to D.C., Guay decided to keep it in Atlanta once he saw Mann speak on CNN about the march.

“I will say that this one is the first time in my life that I felt like an artist,” says Guay. “This is truly what art is about: it’s about putting something in the world that can do something. Not decorating the world. I don’t want to decorate the world anymore. I wanna change the world somehow. Even if it’s just one person, one viewer, someone’s thoughts, something.”

Once Guay has an idea, there’s no stopping him. His story is long; he’s been making art for many years. He’s vacillated in and out of different mediums, from drawing to painting to sculpture to photography to videography to resin, the list goes on. But one consistent thread is this: “no” is never the final answer.

Guay suffers from significant back injuries, and during the period he was assembling “Missed Attendance,” a physician explained to him that he should take a year or so off, not touching anything or doing any sort of lifting. “Everyone was like, ‘Go back to photography,’” remembers Guay. “But I had all this weird momentum inside and I didn’t wanna think that something inside my body could also stop that momentum, so I refused to listen to it. That year when we had so many school shootings… it was getting out of hand.”

After Guay finished painting the desks with blackboard paint, the next step was to place them somewhere people could interact with them, where they could express themselves, similarly to how people engaged with “The Border Wall.” And the no’s were filing in, one right after the other. “Maybe I can put the desks here.” Nope, Coca-Cola owns that land. So Guay goes and talks to Coca-Cola. “Can I put the desks there?” Nope. “I’ll take it to the capitol.” Nope, you’re not putting it there. Guay talks to a state senator. No, you’re not doing it here.

“My dad used to always tell me,” Guay explains, “‘There’s no ‘no’ in the world—you just haven’t found the ‘yes.’ When I talked to Coca-Cola, that’s when I really lost my mind… when someone tells me I can’t do something that in my head I know is gonna be really good. In someone else’s head, they look at it like, ‘Oh, this is some artist who’s gonna start some trouble.’ I should have just shut my mouth and just did it. That’s what I learned. Because I know my intentions with it; other people aren’t going to know that.”

Guay finally reached a gateway “yes” from friend and colleague Natalie Archembaum, who helped Guay get situated with the desks at the capitol. Immediately after, another “no” arrived. “I get there, and I’m not supposed to be lifting anything. Zero,” continues Guay. “And I’m lifting 14 metal desks in a U-haul, carrying them to the capitol with two in my arms, running back and forth trying to get them there before someone steals them, throws them out, confiscates them. During the course of the march, I’m getting kicked out of every place that I put these desks. I moved them around probably 10 or 12 times.”

The day was Sat., March 24, 2018, and 30,000 people turned out to the Atlanta streets, emotions running high in protest of yet another school shooting with no resolution on gun violence in sight.

“A police officer told me I had to get off, move all my stuff, put them back in the truck, and get the truck out of there,” Guay continues as I look back at the desks, imagining them as the blank canvases they once were, being carted about from one place to the next. I imagined students being told “no, you won’t be heard” just as these desks were being told “no, you won’t be seen.” I imagined the flood of 30,000+ people marching towards the capitol, Guay exhausted and out of breath trying to get these desks to land. Here in the story, all pleasantries fell off… and it appeared for the next 10 or 15 minutes at the capitol that day, Guay was suddenly hard of hearing.

“Finally, I got so frustrated I just started stalling everybody and then I saw the march coming with all the people just parading down the road,” he told me. “I threw the desks in the middle of the street, right in the middle of the protest. I went over the barricades with all the desks, I grabbed my friends, and was like, ‘Just throw them in the street!’ We put them right in the middle and I had chalk on top of every desk. The police, of course, were like, ‘You can’t do that, you can’t do that! You need to move all of these!’ And I was like, ‘I can’t hear you, I can’t hear what you’re saying.’”

The contending officer and Guay were both consumed by the crowd and pushed to the side of the street, with the desks sitting square in the middle of the street in front of the capitol. Guay brought signs to instruct people what to do—to use the chalk to write on the desks to express themselves in the wake of the Parkland shooting—but didn’t have time to put them out for people to see. However, no further instruction was needed. Without any question, people took to the desks and ran rampant like ants on a melted Hershey bar.

“Within minutes, all the desks were covered and kids were writing, ‘Please help us, please change,’” recalls Guay. “Right there, just writing all these beautiful thoughts.

“Within minutes, all the desks were covered and kids were writing, ‘Please help us, please change,’” recalls Guay. “Right there, just writing all these beautiful thoughts. I stood back and looked at one of the cops that were the first ones that was adamant about kicking me out of Georgia, basically, and he choked up. He was like, ‘Man, that’s really cool. I didn’t know that’s what you were trying to do.’ This is for people. This isn’t even about me; this is for other people. That’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever experienced as an artist, that moment. I don’t really know how to make that now, moving forward. That’s better than making a hundred paintings that sell in a gallery.”

From this point on in the story, Guay is keenly aware of the power he holds. Leading up to “Missed Attendance,” he said it often felt like the cart was ten miles in front of the horse. Museums have never lined up to showcase his work, no matter the depth and importance of its messages, and that’s just the way it’s been.

Anyway, moving forward. Our conversation carries on, the cart moves, and the next topic presents me with a different set of numbers. As stated by Neta C. Crawford of Brown University in the “Human Cost of the Post-9/11 Wars: Lethality and the Need for Transparency” in Nov. 2018:

“All told, between 480,000 and 507,000 people have been killed in the United States’ post-9/11 wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. This tally of the counts and estimates of direct deaths caused by war violence does not include the more than 500,000 deaths from the war in Syria, raging since 2011, which the U.S. joined in August 2014.”

I turned in my chair and my gaze in the studio shifted to the other side of the room, where I saw large rusted bullet casings chromed with cleaning brand logos on them, like Clorox and OxyClean. My mind raced to think of what this latest exhibit was addressing: America’s philosophy behind war and invading other countries.

“Getting that Hummer,” says Guay, “I thought it would take a lot longer than it did.”

Guay worked tirelessly for about six months to acquire a U.S. military Hummer that was used in battle in the Middle East. A lot of no’s circulated, but of course, that only motivated him further. After several leaps and bounds, he transported the Humvee from a naval base in Alabama to the Murphy Rail Studios in Atlanta. The Hummer was sitting outside the studio underneath a heavy maroon tarp to protect it from rain and nosy spectators. Guay has moved onto the next thing, taking another mundane political conversation and placing it into a happening zone, bringing it to life. The question is: is the audience going to care?

A conversation many don’t arrive at is that the U.S. is currently fighting in seven wars, all of which are part of the War on Terror, which President Obama declared was over in May 2013. That declaration was widely taken out of context; the War on Terror carries its nicknames “The Long War,” “The Forever War,” and “World War III” for a reason. While troops were removed during the Obama administration, drones took their place instead. The numbers behind the human costs of war, it turns out, are difficult to actualize; this is because the numbers of casualties are regularly manipulated to keep the War on Terror looking relatively harmless—and to keep it profitable. In Afghanistan, for example, teenage boys began to be counted as combatants in order to minimize the reported number of civilian deaths. The statistics above come from one of many reports on the numbers behind the War on Terror, and each report offers something different.

“‘The Cost of War’ was created to honor the 4,400 American soldiers and the 480,000 Iraq and Afghanistan soldiers and civilians that have died from the ongoing war in the Middle East,” says Guay in an official press statement regarding the exhibit. “It’s hard to believe that our retaliation to 9/11 was to invade a country that was unrelated to the hijackers, remove their leader, implement new government, and create an unstable environment for the civilians of Iraq and the surrounding regions. America has now spent over $7 trillion on the War on Terror in seven conflicts. Four of these wars are American interventions in the Middle East. And with all this, the world is not any safer than the day after the Towers fell.”

Following our interview, we walked to the back of the studio to the covered vehicle, our feet slapping the pavement on a brutally hot October afternoon. Guay removed the tarp to reveal the war-torn Hummer—the vehicle that was promoted in the U.S. by award-winning advertisements that touted slogans such as “Restore Your Manhood” (which was changed to “Restore the Balance” after receiving criticism) and “Intimidate Men in a Whole New Way”—completely shot up with bullet holes in its windows and on its sides. Inside we found what appeared to be an empty, dusty Dasani bottle, made of light blue plastic with a green top but with slightly unfamiliar branding. While the location where this Hummer was used remains confidential to the U.S. government and unknown to us, this sandblasted water bottle might be the only clue.

Inside the studio, Guay showed me a plethora of toy soldiers (thousands of them) that were to be affixed one by one on the shot and tattered Hummer. By the time the Hummer portion of the exhibit was completed in late November, it carried 28,000 toy soldiers that took several months to place. Its accompanying pieces, such as canteens and soldiers’ helmets, are plated in nickel.

“It was important to me to tangibly show how many have died, on both sides,” says Guay. “I wanted to use toy soldiers, because I played with them as a child. They could spark a small understanding of nostalgia and loss. I did not know how many it would take to cover the entire truck, but I reached 4,400 (the American lives lost) just in the driver’s section of the vehicle. I also nickel plated four pieces on the vehicle—the gas cap, gas can, oil dipstick, and a soldier’s helmet—to symbolize America’s agenda to control oil in the region at any cost.”

If Guay were to attempt to most accurately convey the human costs of the War on Terror with this type of exhibit based on the statistics provided, he would need 36 Hummers.

The Humvee was wrapped and loaded up on a freight truck on Fri., Nov. 29, to make its way to Miami for this year’s Pulse Fair at Art Basel. In a harsh turn of events, the exhibit was mostly destroyed on its way to Florida when the delivery driver cut the outer protective layer off the truck. Many of the soldiers that were solidly glued to the sculpture were torn off and disassembled, altering the vehicle’s story and the impact it holds. After the initial pain of frustration and overwhelm, Guay says he realized this was the reality of the situation this sculpture was speaking to; this is what happens to soldiers’ lives. They are sent off only to return impaired, with damages all too difficult to mend. A project Guay worked on tirelessly since March 2019, and one person’s decision brought the whole thing down.

“In some ways it has taken this for me to understand the true story of what ‘The Cost of War’ is really about,” says Guay in an official statement given to Pulse Art Fair. “It’s about loss, failed attempts, money spent that didn’t fix anything, damaged hearts, missing people, unjust choices, and defeat. It is not about making the perfect object for people to see at an international art fair anymore. It’s about reality: things that get damaged, pieces that need to be picked up, an ongoing war that no one—not even an artist and a sculpture—can begin to explain the losses and damages that have occurred to human lives, soldiers, civilians, and children on all sides.”

In light of this, Guay then announced that 100% of the proceeds from this showing is to be donated to the Gary Sinise Foundation and local VA programs to help disabled veterans, victims, and their families in the U.S.

Guay is not the first to incorporate toy soldiers in political artwork—and he’s not the first to withstand a loss of this magnitude—but the timing and execution of “The Cost of War” carries a lot of weight, with its untimely demise resounding the sculpture’s message even louder. The War on Terror is a doomed and expensive one, and this should, in fact, be a forefront issue in the 2020 election. The amount of money America spends on this futile war is tied to the money we don’t spend at home in communities where it is desperately needed, while hundreds of thousands of soldiers’ and innocent civilians’ lives are lost or destroyed in the process. And for the soldiers who return home, Uncle Sam does next to nothing to de-program them to help heal their deeper wounds.

In a country that is in dire need of reform in all areas—election reform, healthcare reform, prison reform, education reform, to name a few—the War on Terror continues to become more and more costly as it soldiers on, out of sight from our everyday lives.

Rather than intervening and harming others, our country should build a society that works for all people, not just the moguls who profit from the seizing of oil and other resources while killing innocent people. In a country that is in dire need of reform in all areas—election reform, healthcare reform, prison reform, education reform, to name a few—the War on Terror continues to become more and more costly as it soldiers on, out of sight from our everyday lives.

While “The Border Wall” and “Missed Attendance” were interactive exhibits, “The Cost of War” explicitly serves as a protest piece against the U.S. government’s choices and actions. The times we become detached and lose our capacity for empathy do not necessarily speak to a lack of awareness. Our society is perhaps more aware than it’s ever been, with the constant scrolling of news alerts and pings on social media; but it’s also asleep to the weight and the impact of these statistics and the lives behind them. This time, Guay’s work does not arrive as a neutral position, but as a primal scream in a desensitized, disassociated world. And what may have initially appeared to be a loss in the Humvee’s destruction has actually created a greater echo chamber for the truths of war that remain widely unspoken.

And to think at one point, at 17 years old, this man was once willing to burn it all.